Background

Ernst Jünger was born on March 29, 1895 in Heidelberg, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany; the son of Ernst Junger, Sr., a successful businessman and chemist, and of Karoline Lampl.

1917

Lieutenant Ernst Jünger (left) with lieutenant Von Klienitz before a fighting patrol at Regnieville

1925

Ernst Jünger

1925

Ernst Jünger during his time at the University of Leipzig

1942

Jünger, standing with fellow Wehrmacht officer, Colonel Eberhard Wildermuth, on the roof of their Paris hotel

Ernst Jünger in uniform as depicted in the frontispiece of the 3rd edition of In Stahlgewittern

Lieutenant Ernst Jünger with the Pour le Mérite

(Storm of Steel is the memoir of German officer Ernst Jüng...)

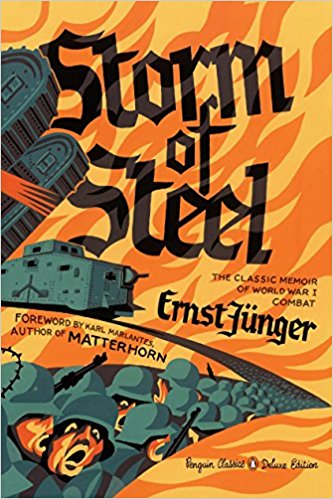

Storm of Steel is the memoir of German officer Ernst Jünger's experiences on the Western Front during the First World War. It was originally printed privately in 1920, making it one of the first personal accounts to be published.

https://www.amazon.com/Storm-Steel-Penguin-Classics-Deluxe/dp/0143108255/?tag=2022091-20

1920

(Written in 1932, just before the fall of the Weimar Repub...)

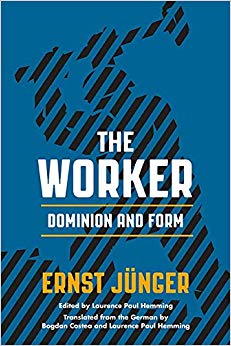

Written in 1932, just before the fall of the Weimar Republic and on the eve of the Nazi accession to power, Ernst Jünger’s The Worker: Dominion and Form articulates a trenchant critique of bourgeois liberalism and seeks to identify the form characteristic of the modern age. Jünger’s analyses, written in critical dialogue with Marx, are inspired by a profound intuition of the movement of history and an insightful interpretation of Nietzsche’s philosophy.

https://www.amazon.com/Worker-Dominion-Form-Ernst-J%C3%BCnger/dp/0810136171/?tag=2022091-20

1932

(Written and published in 1934, a year after Hitler's rise...)

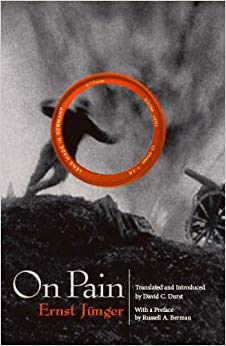

Written and published in 1934, a year after Hitler's rise to power in Germany, Ernst Juenger's On Pain is an astonishing essay that announces the rise of a new metaphysics of pain in a totalitarian age.

https://www.amazon.com/Pain-Ernst-J%C3%BCnger/dp/0914386409/?tag=2022091-20

1934

(In this volume, which bears comparison to the Denkbilder ...)

In this volume, which bears comparison to the Denkbilder of the Frankfurt School, Jünger assembles sixty-three short, often surrealistic prose pieces—accounts of dreams, nature observations, biographical vignettes, and critical reflections on culture and society—providing, as he puts it, "small models of another way of seeing things." Here Jünger experiments with a new method of observation and thinking, uniting lucid and precise observation with the unconstrained receptivity of dreams.

https://www.amazon.com/Adventurous-Heart-Figures-Capriccios/dp/0914386484/?tag=2022091-20

1938

(Ernst Jünger's The Forest Passage explores the possibilit...)

Ernst Jünger's The Forest Passage explores the possibility of resistance: how the independent thinker can withstand and oppose the power of the omnipresent state. A response to the European experience under Nazism, Fascism, and Communism, The Forest Passage has lessons equally relevant for today, wherever an imposed uniformity threatens to stifle liberty.

https://www.amazon.com/Forest-Passage-Ernst-J%C3%BCnger/dp/0914386492/?tag=2022091-20

1951

(Eumeswil is a 1977 novel by the German author Ernst Jünge...)

Eumeswil is a 1977 novel by the German author Ernst Jünger. The narrative is set in an undatable post-apocalyptic world, somewhere in present-day Morocco.

https://www.amazon.com/Eumeswil-Ernst-J%C3%BCnger/dp/0914386522/?tag=2022091-20

1977

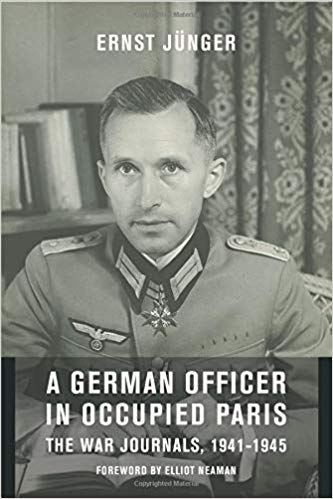

(Ernst Jünger was one of twentieth-century Germany’s most ...)

Ernst Jünger was one of twentieth-century Germany’s most important―and most controversial―writers. Decorated for bravery in World War I and the author of the acclaimed western front memoir Storm of Steel, he frankly depicted war’s horrors even as he extolled its glories. As a Wehrmacht captain during World War II, Jünger faithfully kept a journal in occupied Paris and continued to write on the eastern front and in Germany until its defeat―writings that are of major historical and literary significance.

https://www.amazon.com/German-Officer-Occupied-Paris-Perspectives/dp/0231127405/?tag=2022091-20

1986

Ernst Jünger was born on March 29, 1895 in Heidelberg, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany; the son of Ernst Junger, Sr., a successful businessman and chemist, and of Karoline Lampl.

Junger went to school in Hannover from 1901 to 1905, and during 1905 to 1907 to boarding schools in Hanover and Brunswick. From 1907 to 1912 went to school in Wunstorf, where he developed his passion for adventure novels and for entomology. He spent some time as an exchange student in Buironfosse, Saint-Quentin, France, in September 1909.

In 1913, Jünger became a student at the Hamelin gymnasium. In November of the same year, he travelled to Verdun and enlisted in the French Foreign Legion for five years. After being dismissed from the Legion, Jünger was sent to a boarding school in Hanover.

In 1923, Jünger studied zoology and botany at the Universities of Leipzig and Naples.

In 1914 Jünger volunteered for the German Army at the outbreak of World War I and served as an officer on the Western Front throughout the conflict.

After the war Jünger first wrote a series of essentially autobiographical war diaries, In Stahlgewittern (1920; In Storms of Steel), Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis (1922; Battle as Inner Experience), Das Wäldchen 125 (1925; Wood 125), and Feuer und Blut (1926; Fire and Blood). He blends stark realism— indeed brutality—of detail with a language that is often intoxicated, highly stylized, or apodictic; he glorifies the primacy of instinctual life and imputes to Western democracy "the metaphysics of the restaurant-car."

Involved in politics in the late 1920s, in 1931 Jünger published Die totale Mobilmachung (Total Mobilization) and in 1932 Der Arbeiter (The Worker). His concept of the total mobilization of society and his view of the worker as a mere integer in a technological world have an antihumanistic and indeed totalitarian cast. Analogies with fascistic doctrines may be easily discerned in these works that define freedom as total identification with the mass will. But Jünger was not a member of the Nazi party; a group with which he had connections, the National Bolsheviks, was broken up by the Gestapo in 1937. He himself, however, was protected by his high military friends.

Jünger's novel Auf den Marmorklippen (1939; On the Marble Cliffs), his best-known work, shows an evolution of attitude and is generally regarded as an allegorical critique of Hitlerism and of the totalitarian state. The book appeared in December 1939 and was suddenly banned in the spring of 1940. Auf den Marmorklippen portrays the violence with which a peaceful culture, reflected in the secluded lives of two practicing botanists, is overrun and destroyed by the hordes of a tyrant known as the Head Forester.

Jünger served in the German army once more, from 1939 to 1944. His subsequent novels, Heliopolis (1949) and Gläserne Bienen (1957; Glass Bees), restate the central issue of the conflict between reason and instinct, contemplation and action. After 1950 Jünger lived in self-imposed isolation in West Germany while continuing to publish brooding, introspective novels and essays on various topics. In such later books as Aladins Problem (1983), he tended to condemn the militaristic attitudes that had led to Germany’s disastrous participation in the World Wars. Jünger’s Sämtliche Werke (“Complete Works”) were published in 18 volumes from 1978 to 1983.

Ernst Jünger was one of most prominent German authors of the twentieth century, who pioneered the prose style now called magic realism. He was also one of the main theorists of the conservative revolution and made a significant contribution to military theory. Jünger made his literary name with Storm of Steel (1920), a bestselling record of trench fighting written up from war diaries.

For his outstanding military service during World War I Jünger was awarded the House Order of Hohenzollern, the Wound Badge 1st Class and the Pour le Mérite, the highest military decoration of the German Empire. He was the last living bearer of the military version of the order of the Pour le Mérite.

In 1985, to mark Jünger's 90th birthday, the German state of Baden-Württemberg established Ernst Jünger Prize in Entomology. It is given every three years for outstanding work in the field of entomology.

(In this volume, which bears comparison to the Denkbilder ...)

1938(Written in 1932, just before the fall of the Weimar Repub...)

1932(Written and published in 1934, a year after Hitler's rise...)

1934(Ernst Jünger's The Forest Passage explores the possibilit...)

1951(Storm of Steel is the memoir of German officer Ernst Jüng...)

1920(Ernst Jünger was one of twentieth-century Germany’s most ...)

1986(Eumeswil is a 1977 novel by the German author Ernst Jünge...)

1977A year before his death, Jünger was received into the Catholic Church and began to receive the Sacraments.

During the interwar years Ernst Jünger contributed to several right-wing journals, and criticized both the Weimar Republic and the National Socialists. But he was not impressed with Nazi Party (NSDAP), as well, and refused an offer from Adolf Hitler to take a seat in the Reichstag twice as well as membership in the Nazified German Academy. By 1943 he had turned decisively against Nazi totalitarianism and its goal of world conquest.

Although he had been cleared of the accusation of any fascist or Nazi sympathies since the 1950s, and he never showed any sympathy to the political style of "blood and soil" popular in the Third Reich, Jünger's national conservativism and his ongoing role as conservative philosopher and icon made him a controversial figure in the eyes of the German Marxist Left.

World War I left a lasting impression on Jünger. Three characteristics of that conflict shaped his view of the world: the destructive power of the new armaments, their lethality, and the consequential subordination of individual courage to the power of machines. In the end whoever made the best use of the war industry would be victorious. The new weapons changed the character of killing and dying because violence was inflicted at a distance and on a massive scale. The person who falls is not seen, his last breath is not heard, and his blood does not splatter the aggressor. At a distance death is wrapped in indifference and anonymity. The slaughter becomes more sudden, massive, and above all reciprocal.

Jünger's first book, In Stahlgewittern (1920), is a memoir of his four years on the western front. In this work he showed his ideological embrace of technology even as he struggled with the tension between human will and the power of mechanized warfare. His interpretation of the larger meaning of the war is presented in Die Totale Mobilmachung (1931). The title refers to the fact that the mobilization of all forces, including industrial and productive capacity, becomes decisive in the definition of conflicts. Jünger read these phenomena as signs of a historical transition. A new reality was emerging, dominated by the "figure of the worker."

In his single most influential work, Der Arbeiter: Herrschaft und Gestalt (1932), Jünger developed his vision of a radically antibourgeois future based on total mobilization. This work often is interpreted as a totalitarian or authoritarian rebuttal of the bourgeois conception of freedom, the market economy, and the liberal nation-state. In it Jünger envisioned the "worker" as the destiny of the coming age, to be characterized by technocratic control in place of the anarchy of liberal individualism. The bourgeois individual will be replaced by the worker "type" in an "organically constructed" political order. Freedom will become identical to obedience. Individuals will be folded into the unity of the whole. Both this metaphysical substructure, or gestalt, of the worker and Jünger's political philosophy of detachment deeply influenced Heidegger.

Der Arbeiter also is predicated on Jünger's concept of "heroic realism," which seeks out the danger that bourgeois reason domesticates by making all risk calculable. In opposition to bourgeois concerns for comfort and convenience, modern technology has an inner destructive character as "the way in which the gestalt of the worker mobilizes the world". The conversion of all activity into some kind of work is a manifestation of the predominance of this work character. Indeed, the term worker does not so much designate a class or social affiliation as it defines a Lebenstand, or "state of life," to which Jünger attributed the formative power emerging in history. Jünger thus disassociates his conception from the proletariat of Marxism. It is indicative of Jünger's political complexity that Der Arbeiter was regarded by the right as communistic and by the left as fascist.

Total mobilization and the predominance of the worker express a new reality in which the efficacy of an action has priority over its legitimacy. In this sense Jünger's philosophy is aligned with Friedrich Nietzsche's (1844–1900) "active nihilism" and Heidegger's "empire of technics." In fact, Jünger's greatest influence on Heidegger stems from this metaphysical analysis of technology as an essential way of being in the world.

Jünger's Auf den Marmorklippen (1939) is a covert criticism of National Socialist tyranny. A poetic and obscure book that seems to aestheticize violence, it presents types more than concrete characters and in that way achieves a general critique of totalitarianism. Indeed, by the time of the 1938 Krystall Nacht (the Nazi attack on Jewish businesses in Germany) it was evident to Jünger that the National Socialist regime was essentially the same crude form of proletariat totalitarianism as the Bolshevik regime in Russia.

Gläserne Bienen (1957) raised the moral dilemma of the use of technology in society and foreshadowed modern developments in robotics and nanotechnology, presenting a world where "even the molecules were controlled." The novel questioned how people might retain a sense of place and identity in light of the accelerating pace at which the old is replaced by the new. It also expressed a growing contempt for both an impersonalized, bureaucratized society and the scientific, materialistic worldview that discredits meaning and purpose and cosiders humans to be lowly cosmic accidents.

Jünger did not produce a systematic philosophy, but his complex, inconsistent, and fierce independence often captured an emerging technoscientific world in an indifferent but therefore critical gaze. Jünger disdained any nostalgic form of antitechnology but refused to hail a world of sustained technological progress culminating in rationality and moral decency. His heroic realism is a qualified yes that comes out of an encounter with the emerging: It is as useless to attempt to avoid the power of modern technology as it is naive to ignore its enormous potential for destruction.

Quotations:

''So I swear to myself in the future to fall alone in freedom rather than to accompany the servants on the path to triumph.''

"Today only the person who no longer believes in a happy ending, only he who has consciously renounced it, is able to live. A happy century does not exist; but there are moments of happiness, and there is freedom in the moment."

"The anarchist, as the born foe of authority, will be destroyed by it after damaging it more or less. The anarch, on the other hand, has appropriated authority; he is sovereign. He therefore behaves as a neutral power vis-à-vis state and society. He may like, dislike, or be indifferent to whatever occurs in them. That is what determines his conduct; he invests no emotional values."

"It has always been my ideal in war to eliminate all feelings of hatred and to treat my enemy as an enemy only in battle and to honour him as a man according to his courage."

"I am an anarch – not because I despise authority, but because I need it. Likewise, I am not a nonbeliever, but a man who demands something worth believing in."

"Freedom is based on the anarch’s awareness that he can kill himself. He carries this awareness around; it accompanies him like a shadow that he can conjure up. “A leap from this bridge will set me free."

"In my experience, I have found that creativity demands a vigilant mind, which is weakened by the influence of drugs."

"The partisan wants to change the law, the criminal break it; the anarch wants neither. He is not for or against the law. While not acknowledging the law, he does try to recognize it like the laws of nature, and he adjusts accordingly."

Ernst Jünger went to literary parties, visited Picasso and Braque, and hunted out rare editions. A learned observer of nature, he enjoyed parks and the countryside, where he collected beetles (he was an expert).

Ernst Jünger's photobooks are visual accompaniments to his writings on technology and modernity. The seven books of photography Jünger published between 1928 and 1934 are representative of the most militaristic and radically right wing period in his writing.

Throughout his life Jünger had experimented with drugs such as ether, cocaine, and hashish; and later in life he used mescaline and LSD.

In 1925, Ernst Jünger married Gretha von Jeinsen. They had two children, Ernst Jr. and Alexander. In 1960, his first wife died and in 1962 he married Liselotte Lohrer. Jünger's second son, Alexander, a physician, committed suicide in 1993.

(March 20, 1917 - August 31, 2010)

(March 14, 1906 - November 20, 1960)