Background

Friedrich Ratzel was born on April 30, 1844, in Karlsruhe, Germany. The father of Friedrich Ratzel was the manager of the household staff of the Grand Duke of Baden.

Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Friedrich Ratzel went to Heidelberg University to study zoology.

University of Jena, Jena, Thuringia, Germany

Friedrich Ratzel went to the University of Jena to study zoology.

Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Friedrich Ratzel went to the University of Berlin and in 1868 Ratzel presented a thesis on the characteristics of worms.

Friedrich Ratzel

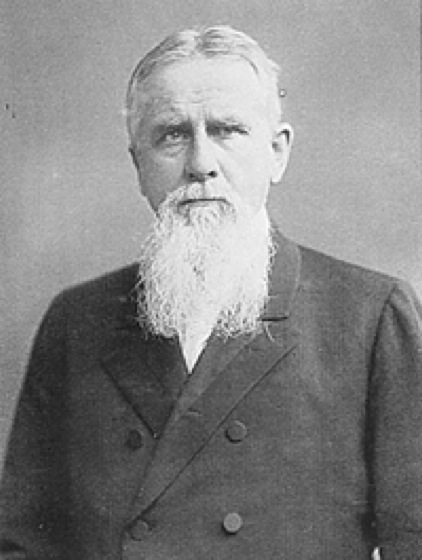

Friedrich Ratzel, German geographer and ethnographer .

Friedrich Ratzel, German geographer and ethnographer.

ethnographer geographer scientist

Friedrich Ratzel was born on April 30, 1844, in Karlsruhe, Germany. The father of Friedrich Ratzel was the manager of the household staff of the Grand Duke of Baden.

Ratzel went to a high school in Karlsruhe for 6 years before he was apprenticed to an apothecary in 1859. He stayed with him until 1863, when he went to Rappeswyl on the Lake of Zurich, Switzerland, where he began to study the classics. After a further year as an apothecary at Mörs near Krefeld in the Ruhr area (1865-1866), he spent a short time at the high school in Karlsruhe and became a student of zoology at the universities of Heidelberg, Jena, and Berlin. In 1868 Ratzel presented a thesis on the characteristics of worms and, a year later, a book on the work of Charles Darwin, whose Origin of Species had appeared in 1859.

Ratzel subsequently traveled in the Mediterranean countries and assisted the French naturalist Charles Martin at Sete and Montpellier. After his recovery from wounds suffered in the Franco-Prussian war, he studied for a short while at Munich, where he met the geologist Karl von Zittel and Moritz Wagner, the curator of the university ethnographical museum, whose ideas on the importance of the migration of species made a lasting impression on him.

In 1871 Ratzel traveled widely in the Danube countries, the Alps, and Italy. In 1874 and 1875 he made a long tour of North America, where he was especially interested in the black population, the dwindling habitation areas of the American Indians, and the inflow of the Chinese into California. He wrote six large volumes on North America, treated it in parts of other works, and produced a shorter treatise entitled Das Meer als Quelle der Volkergrosse (1900).

On his return to Europe, Ratzel began a full-time academic career, lecturing on geography at the Technische Hochschule in Munich. He began to criticize Darwin’s theory of natural selection and Haeckel’s views on evolution but always remained convinced of the application of concepts of organic evolution to human societies. His lectures covered a wide range of geographical topics; and although he was mainly interested in human aspects, he also wrote extensively on physical aspects such as earth-pillars, limestone surfaces, and the snow line. During his eleven years at Munich, Ratzel produced the first volume of Antliropo-geographie (1882) and the first two volumes of his Volkerkunde (1885-1886), as well as at least 160 shorter items.

In 1886 Ratzel accepted the chair of geography at Leipzig, succeeding Ferdinand von Richthofen. During his years at Leipzig (1886-1904), he wrote thirteen books and about 350 sizable articles. His shorter articles range from useful observations on physical phenomena, such as the measurement of the density of snow (1889), to numerous obituaries and polemics. They also include several important analyses of his concepts of Lebensraum and “scientific political geography.”

An accurate assessment of the scientific importance of Ratzel’s work is difficult because of his changes of view, his enormous output, and the emotions aroused by the disastrous political results that stemmed from perverted versions of his concepts.

The bridge between Ratzel’s ethnography and geography appeared clearly in his Antliropo-geographie, in which the central themes are spatial distributions of a culture and their dependence on the physical environment and on migrations and borrowings over the centuries. The first volume deals mainly with the causes or dynamic aspects of human distributions, and the second emphasizes the static aspects. The development of a society or a people is considered to be governed largely by its situation relative to other geographical phenomena, by the space in which it moves, and by the frame that limits those movements and is itself related to the development of adjacent peoples.

In his later years, Ratzel took a keen interest in contemporary philosophy, and in his Politische Geographie (1897) he attempted to combine practical politics with physical-philosophical material. He began to favor the idea of a “sense of space” that influences the collective psychology of its inhabitants, and believed that great space confers great rights and virtues. This important book was probably the first political geography to tackle each problem methodically and to treat the subject scientifically.

Apart from his major works he published many important articles on political geography and the spatial relationships of geographical phenomena. The most famous was the article “Der Lebensraum. Eine biogeographische Studie” (1901), which summarized his earlier efforts to associate organic activities with the physical environment and to link biology and biogeography with human geography.

Besides the patient amassing of knowledge on terrestrial objects and phenomena and their spatial distribution, Ratzel’s main scientific accomplishments were in ethnography and human geography. His chief contribution to ethnography was to popularize the importance of the diffusion of culture by migration and by borrowing. He assumed, often correctly, that agreement of form which was independent of the nature, material, and function of an object or artifact indicated a historical connection or borrowing.

Another Ratzel’s achievement was in originating the concept of Lebensraum, or “living space,” which relates human groups to the spatial units where they develop.

The book for which Ratzel is acknowledged all over the world is Anthropogeographie. In Anthropogeographie he considered population distribution, its relation to migration and environment, and also the effects of environment on individuals and societies. His other works included Die Erde und das Leben: Eine vergleichende Erdkunde (1901–02; “Earth and Life: A Comparative Geography”), Politische Geographie (1897; “Political-Geography”), and a political-geographical study of the United States (1893). His essay “Lebensraum” (1901), often cited as a starting point in geopolitics, was a study in biogeography.

Ratzel expressed his views by publishing in 1869 a popular history of creation, which showed an uncritical acceptance of Darwin’s main concepts and an obvious reliance on the views of Haeckel.

Ratzel’s deep concern with spatial relations and especially with the covariants of cultural distributions were truly fruitful concepts. When carried to extremes their political aspects could be perverted into crude master-race theories, which had a disastrous effect during the rise of Hitler. Ratzel did occasionally criticize such extreme racial views, but his criticisms were drowned amid the mass of his writings.

Ratzel’s ideas on man-milieu relationships could, if advertised more clearly, have developed into modern notions on the cultural landscape and on the conservation of the environment. Similarly, his ideas on spatial economic and cultural distributions were among the most fruitful concepts ever devised in scientific human geography. The Lebensraum concept, as he showed, was applicable to units of different size.

His essays on the sites and development of cities and on the hinterlands of seaports (in which he defined the areal extent and overlap of the limits in regard to nature, politics, delivery, supply or production, and traffic) were the precursors of studies that appeared after 1930. Despite his misfortunes at the hands of extremists, Ratzel must be regarded as the true founder and greatest single contributor to the development of modern human geography.

Quotations:

"Arbitrary rule has its basis, not in the strength of the state or the chief, but in the moral weakness of the individual, who submits almost without resistance to the domineering power. "

"A philosophy of the history of the human race, worthy of its name, must begin with the heavens and descend to the earth, must be charged with the conviction that all existence is one-a single conception sustained from beginning to end upon one identical law. "

When Ratzel studied for a short while at Munich, where he met Moritz Wagner, the curator of the university ethnographical museum, his ideas on the importance of the migration of species made a lasting impression on him.