Background

Henry Baker was born on 8 May 1698, in Chancery Lane, London. His father, William, was a Clerk in Chancery, and his mother, the former Mary Pengry, was “a midwife of great practice.”

1744

In 1744 Baker received the Copley gold medal for microscopical observations on the crystallization of saline particles.

the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, London, SW1 United Kingdom

Baker became a fellow of the Royal Society on March 1741.

The Society of Antiquaries of London (SAL), Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, England, United Kingdom

In January 1740, Baker became a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.

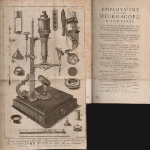

From the Employment for the Microscope by Henry Baker.

https://www.amazon.com/microscope-made-easy-microscopes-discoveries-ebook/dp/B07D5BDBGZ/?tag=2022091-20

1743

microscopist naturalist scientist

Henry Baker was born on 8 May 1698, in Chancery Lane, London. His father, William, was a Clerk in Chancery, and his mother, the former Mary Pengry, was “a midwife of great practice.”

At the age of fifteen, Baker was apprenticed to a bookseller whose business later passed into the hands of Robert Dodsley, the printer of Baker’s microscopical works.

In 1720, at the close of his indentures, Baker went to stay with John Forster, a relative and an attorney, whose daughter had been born deaf. Baker felt inspired Lo teach the child to read and speak, and was so successful that he became in great demand as a teacher both of the deaf and dumb, and of those with speech defects. He amassed a considerable fortune, and possibly it was for financial reasons that he kept his teaching methods secret. Four manuscript volumes of exercises written by his pupils have, however, survived, and are in the library of the University of Manchester.

Baker’s work with the deaf attracted the interest of Daniel Defoe, one of whose early novels, The Life and Adventures of Duncan Campbell (1720), was about a deaf conjurer. This book shows that Defoe was familiar with the methods for teaching the deaf used by John Wallis. In 1728, Defoe and Baker had established the Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal, Baker using the pseudonym Henry Stonecastle. The magazine existed until 1746, and Baker was in charge of its production and a frequent contributor until 1733. His annotated volume containing copies of the journal, from the first copy until April 1735, is now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Baker’s early literary efforts also included several volumes of verse, both original and translated. In 1727 he published The Universe: a Philosophical Poem intended to restrain the Pride of Man, which was much admired and reached the third edition, incorporating a short eulogy of the author, in 1805.

In January 1740, Baker became a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, and in March 1741 a fellow of the Royal Society. For the next seventeen years, he was a frequent contributor to the Philosophical Transactions, on subjects as diverse as the phenomenon of a girl “able to speak without a tongue” and the electrification of a myrtle tree. Microscopical examinations of water creatures and fossils were, however, the subject of the majority of his papers and were included in his books on microscopy. In 1742 there was considerable interest among fellows of the Royal Society in the freshwater polyp (Hydra viridis) as a result of the recent discovery and description of this animal by Abraham Trembley, and with Martin Folkes Baker carried out experiments on this animalcule which he published in 1743 under the title An Attempt towards a Natural History of the Polype. The first edition of The Microscope Made Easy appeared in 1742; it ran to five editions in Baker’s lifetime and was translated into several foreign languages.

Baker was an indefatigable correspondent with scientists and members of philosophical societies all over Europe. He introduced the alpine strawberry into England with seeds sent to him from a correspondent in Turin, and the rhubarb plant (Rheum palmatum) sent from a correspondent in Russia. Eleven years after the appearance of The Microscope Made Easy, Baker published a second microscopical work, Employment for the Microscope, which was as successful as its predecessor. In 1754 the Society for the Encouragement of Arts Manufactures and Commerce was established, and Baker was the first honorary secretary. He died in his apartments in the Strand at the age of seventy-six and left the bulk of his property to his grandson, William Baker, a clergyman.

He bequeathed the sum of £100 to the Royal Society for the establishment of an oration, which was called the Bakerian Lecture. Among notable Bakerian lecturers in the fifty years following Baker’s death were Tiberius Cavallo, Humphry Davy, and Michael Faraday. Baker’s considerable collection of antiquities and objects of natural history was sold at auction in the nine days beginning 13 March 1775.

One of Henry Baker's main achievements was in his contribution of many memoirs to the Transactions of the Royal Society. Among his publications were The Microscope made Easy (1743), Employment for the Microscope (1753), where he noted down the presence of dinoflagellates for the first time as "Animalcules which cause the Sparkling Light in Sea Water", and several volumes of verse, original and translated, including The Universe, a Poem intended to restrain the Pride of Man (1727).

Apart from his work as an instructor in the techniques of microscopy, Baker’s most important scientific achievements were the observation under the microscope of crystal morphology, for which he received the Copley Medal, and his account of an examination of twenty-six bead microscopes bequeathed to the Royal Society by Antony van Leeuwenhoek. His measurements of these unique microscopes (lost during the nineteenth century) are the most valuable historical material. The Copley Medal of the Royal Society was awarded to Baker in 1744 “for his curious Experiments relating to the Crystallization or Configuration of the minute particles of Saline Bodies dissolved in a menstruum.”

Another Baker's achievement was in the establishment of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce in 1754 (later the Society of Arts).

Throughout his life, Baker had a keen interest in natural philosophy, as well as was known for his pious approach to the wonders of nature. He regarded the microscope with reverence, as a means to the deeper appreciation of the wonders of God’s world. “Microscopes,” he wrote in the introduction to The Microscope Made Easy, “furnish us as it were with a new sense, unfold the amazing operations of Nature,” and give mankind a deeper sense of “the infinite Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of Nature’s Almighty Parent.” The Microscope Made Easy is divided into two parts, the first dealing with the various kinds of microscopes, how each may be best employed, the adjustment of the instrument, and the preparation of specimens. Part II has chapters devoted to the examination of various natural objects, in the manner of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia - e.g., the flea, the poison of the viper, hairs, and pollen. Part 1 of Employment for the Microscope is devoted to the study of crystals, and Part II is a miscellany of Baker’s microscopical discoveries. Both books were deliberately written for the layman.

In January 1740, Baker became a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, and in March 1741 a fellow of the Royal Society.

Henry Baker was in many respects a typical natural philosopher of the eighteenth century. His interests ranged widely, and his skills were equally various; he was by no means dedicated to one branch of study, nor did he do research in the modern sense. Yet he deserved the title “a philosopher in little things”; and he had the rare gift of communicating his knowledge of, and above all his enthusiasm for, the microscope to others. This was what made his two books so widely popular.

Baker married Daniel Defoe’s youngest daughter, Sophia, in 1729. They had two sons, but neither of them had a successful career, and both predeceased their father.

Under the name of Henry Stonecastle, Baker was associated with Daniel Defoe in starting the Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal in 1728.

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek is commonly known as "the Father of Microbiology", and one of the first microscopists and microbiologists. Van Leeuwenhoek is best known for his pioneering work in microscopy and for his contributions toward the establishment of microbiology as a scientific discipline.