Background

Davy was born on December 17, 1778, in Penzance, Cornwall, to a family of modest means. He was the eldest of the five children of Robert Davy, a woodcarver, and his wife Grace Millett.

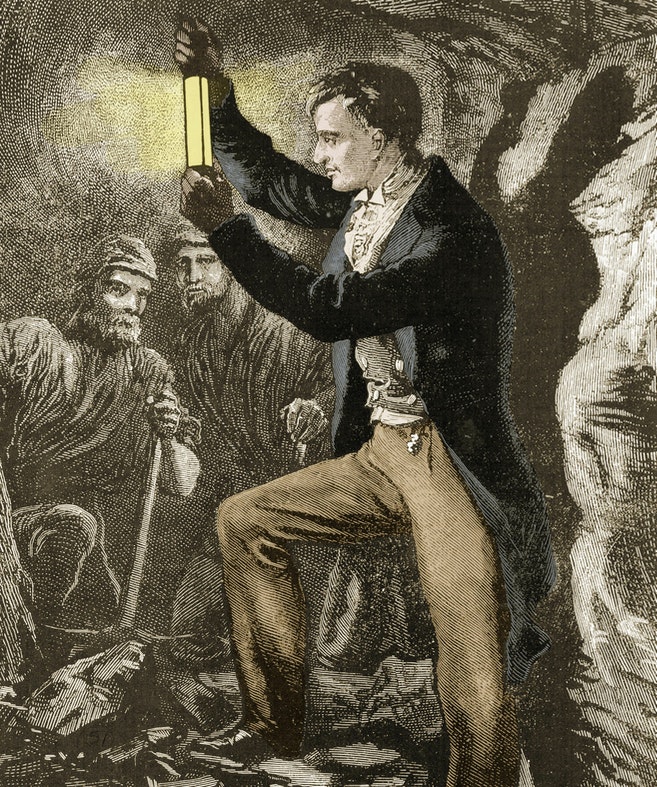

The Davy lamp

Statue of Davy in Penzance, Cornwall, holding his safety lamp

Portrait of Humphry Davy

Portrait of Humphry Davy

Portrait of Humphry Davy with the Davy lamp

Portrait of Humphry Davy

Davy was born on December 17, 1778, in Penzance, Cornwall, to a family of modest means. He was the eldest of the five children of Robert Davy, a woodcarver, and his wife Grace Millett.

Humphry was well educated, but he was also naturally intelligent and curious, and those traits often manifested in the fiction and poetry he wrote at an early age.

At the age of six Davy was sent to the grammar school in Penzance. In 1793 John Tonkin paid for his education in Truro Grammar School. In 1793 Davy finished his education under the Rev. Dr. Cardew.

Davy's obvious talents attracted the attention of Gregory Watt and Davies Giddy (later Gilbert), both of whom recommended him to Dr. Thomas Beddoes for the position of superintendent of the newly founded Pneumatic Institution in Bristol. He worked there from October 1799 to March 1801.

The Pneumatic Institution was investigating the idea that certain diseases might be cured by the inhalation of gases. Davy, sometimes perilously, inhaled many gases and found that the respiration of nitrous oxide produced surprising results. Inhalation of "laughing gas," as it was soon called, became a novel form of entertainment, although nearly 50 years passed before it was actually used as an anesthetic. Davy also experimented with the newly invented voltaic pile or battery.

Davy left Bristol to become the lecturer in chemistry at the Royal Institution in London. Sir Joseph Banks and Count Rumford had founded the Royal Institution in 1799 as a research institute and as a place for educating young men in science and mechanics. Here Davy's genius emerged full-blown. Not only did his brilliant lectures attract a fashionable and intellectual audience, but he also continued his electrical research. In 1806 he showed that there was a real connection between electrical and chemical behavior. In 1807 he electrolyzed molten potash and soda and announced the isolation of two new elements, naming them potassium and sodium. In 1808 he isolated and named calcium, barium, strontium, and magnesium. Later he showed that boron, aluminum, beryllium, and fluorine existed, although he was not able to isolate them.

Lavoisier had claimed that a substance was acid because it contained oxygen. Davy doubted the validity of this claim and in 1810 showed that "oxymuriatic acid gas" was not the oxide of an unknown element, murium, but a true element, which he named chlorine.

Davy was knighted by King George III in 1812.

Napoleon I invited him to visit France, even though the two countries were at war. Sir Humphry and his wife went to France in 1813, taking with them as valet and chemical assistant the 22-year-old Michael Faraday. The French presented them with a curious substance isolated from sea-weed, and Davy, working in his hotel room, was able to show that this was another new element, iodine. When he returned to England, he was asked by a group of clergymen to study the problem of providing illumination in coal mines without exploding the methane there. Davy devised the miner's safety lamp and gave the invention to the world without attempting to patent or otherwise exploit it. Working in another area, he demonstrated how electrochemical corrosion could be prevented.

In 1820, after Sir Joseph Banks had died, Sir Humphry was made president of the Royal Society. He began the needed internal reform of the society, but bad health forced him to resign in 1827. The remaining years of his life he spent wandering about the Continent in search of a cure for the strokes from which he suffered.

Davy is most famous for his discoveries of potassium, sodium, chlorine, and other elements using powerful voltaic batteries. Through his research, he established the science of electrochemistry. Davy studied the therapeutic uses of various gases, after which he made several reports on the effects of inhaling nitrous oxide (laughing gas). He invented the Davy lamp, a device that greatly improved safety for miners in the coal industry.

For his research, Davy received numerous awards and honors, among them the Copley Award, the Royal Society’s Royal Medal, and election to the presidency of the Royal Society. He was also knighted (1812) and made a baronet (1818).

Davy Medal for outstanding discoveries in any branch of chemistry bears his name. The Davy lunar crater is also named after him.

Davy's religion was rather vague, though intense and personal. He included both poetic and religious commentary in his lectures, emphasizing that God's design was revealed by chemical investigations.

In politics, as in science, Davy adopted the motto of the Royal Society, "nullius in verbal," he followed no leader and belonged to no party; he declared of himself he "had no strong political bias." Davy kept himself free to entertain such views as appeared to him best warranted by facts and circumstances. And yet he was not lukewarm in politics, nor wavering in principles; his principles were those of constitutional liberty, to which he was devotedly attached.

Davy prepared (and inhaled) nitrous oxide (also known as laughing gas) to test its disease-causing properties, and his work led to an appointment as chemical superintendent of the Pneumatic Institution in 1798. From that position he explored such areas as oxides, nitrogen, and ammonia, and in 1800 Davy published his findings in the book "Researches, Chemical and Philosophical."

Davy next dived into electricity experiments, namely exploring the electricity-producing properties of electrolytic cells and the chemical implications of those cells' processes. These experiments were detailed in "On Some Chemical Agencies of Electricity," a lecture Davy delivered in 1806. That work led to further discoveries regarding sodium and potassium and the discovery of boron. Also along this trajectory, Davy parsed out why chlorine serves as a bleaching agent and did research for the Society for Preventing Accidents in Coal Mines, which led to the invention of a safe lamp for coal miners, dubbed the Davy lamp.

Quotations:

"Nothing is so dangerous to the progress of the human mind than to assume that our views of science are ultimate, that there are no mysteries in nature, that our triumphs are complete and that there are no new worlds to conquer."

"Life is made up, not of great sacrifices or duties, but of little things, in which smiles and kindnesses and small obligations, given habitually, are what win and preserve the heart, and secure comfort."

"The more we know, the more we feel our ignorance; the more we feel how much remains unknown."

"You are now in a state in which a fly would be whose microscopic eye was changed to one similar to that of man: and you are wholly unable to associate what you see with your former knowledge."

"Nothing is so fatal to the progress of the human mind as to suppose our views of science are ultimate; that there are no mysteries in nature; that our triumphs are complete; and that there are no new worlds to conquer."

Humphry was a President of the Royal Society from 1820 to 1827. He also was a member of the Royal Irish Academy, and Fellow of the Geological Society.

An exuberant, affectionate, and popular lad, of quick wit and lively imagination, Humphry Davy was fond of composing verses, sketching, making fireworks, fishing, shooting, and collecting minerals. He loved to wander, one pocket filled with fishing tackle and the other with rock specimens. He never lost his intense love of nature and, particularly, of mountain and water scenery.

Quotes from others about the person

"If he had not been the first chemist he would have been the first poet of his age." - Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Davy married a wealthy widow, Jane Apreece. While he was generally acknowledged as being faithful to his wife, their relationship was stormy, and in later years he traveled to continental Europe alone. Their marriage was childless.

Beddoes, who had established at Bristol a 'Pneumatic Institution,' needed an assistant to superintend the laboratory. Gilbert recommended Davy. In 1798 Davy took a position at Thomas Beddoes's Pneumatic Institution, where the use of the newly discovered gases in the cure and prevention of disease was investigated.

Davy was befriended by Davies Gilbert, who lived with Davy as a lodger and would serve as a major influence on Davy's life of science. Gilbert allowed Davy to use a library and well-equipped chemical laboratory, and Davy began experimenting, chiefly with gases.

In 1812, Faraday attended four lectures given by Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution. Faraday subsequently wrote to Davy asking for a job as his assistant. Davy turned him down but in 1813 appointed him to the job of chemical assistant at the Royal Institution. A year later, Faraday was invited to accompany Davy and his wife on an 18-month European tour, taking in France, Switzerland, Italy, and Belgium and meeting many influential scientists.

Davy later accused Faraday of plagiarism, causing Faraday to cease all research in electromagnetism until his mentor's death.

Davy became close friends with Gregory Watt, James Watt, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Robert Southey, all of whom became regular users of nitrous oxide (laughing gas), to which Davy became addicted.