Background

James Frazer was born on January 1, 1854, in Glasgow, Scotland. He was the son of Daniel F. Frazer, a chemist, and his wife, Katherine Brown.

University of Glasgow, University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ, United Kingdom

James attended the University of Glasgow from 1869 to 1874.

Trinity College, Cambridge CB2 1TQ, United Kingdom

After taking his degree at Glasgow James matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge. He took second place in the classical tripos of 1878.

United Kingdom

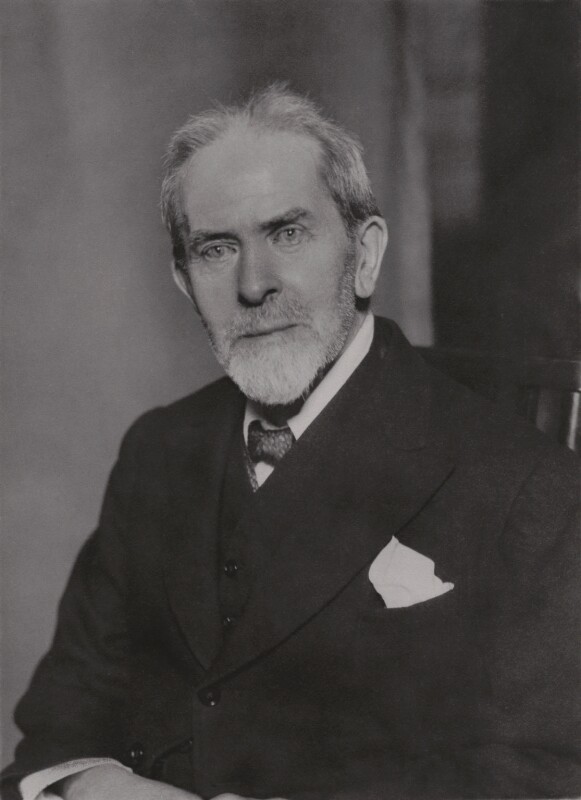

James George Frazer

United Kingdom

James George Frazer

United Kingdom

James George Frazer

United Kingdom

James George Frazer

anthropologist folklorist scientist scholars

James Frazer was born on January 1, 1854, in Glasgow, Scotland. He was the son of Daniel F. Frazer, a chemist, and his wife, Katherine Brown.

James attended the University of Glasgow from 1869 to 1874. He did brilliantly at Glasgow but soon realized that although Scottish education gave him a broader background than an English one would have, its standards were not as high. After taking his degree at Glasgow he, therefore, matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge. He took second place in the classical tripos of 1878. He also studied law but didn't practice it.

After graduating from Trinity College, James was elected a fellow of the college in 1879. He remained at Cambridge for the rest of his life, except for an appointment as professor of social anthropology at Liverpool University in 1907, which he resigned after a year.

Frazer maintained his interest in the classics, and his only original research was some archaeological fieldwork undertaken for his translation of Pausanius’ Description of Greece, published in 1898: his anthropological work was deeply rooted in his classical studies.

In 1883 William Robertson Smith came to Cambridge as professor of Arabic and aroused Frazer’s interest in anthropology. He was also editor of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and asked Frazer to write a number of articles, first on classical subjects and later, after Frazer had read E. B. Tylor’s Primitive Culture, on “Totem” and “Taboo,” both published in 1888. These were later expanded into the four-volume work Totemism and Exogamy. As early as 1885 Frazer read to the Anthropological Institute a paper on burial customs which clearly showed the influence of Tylor, and in 1890 he published the first edition of The Golden Bough. This title was taken from book VI of the Aeneid, and the work started as an investigation of the rites surrounding the priest at the Grove of Diana in Aricia. But in the process of compilation, it was expanded into a detailed comparative study similar to Primitive Culture but was better documented and included more material on rites and practices in European countries which appeared similar to those of more primitive societies. This was extended further into a work of twelve volumes and an appendix. Volume XII was an alphabetical bibliography of some 5,000 items in most European languages, of which less than 1 percent were asterisked to indicate that Frazer had not seen them himself.

Frazer was invited to Liverpool to occupy the first post of professor of social anthropology in any university, which he held for one year from 1907 to 1908, giving an inaugural lecture entitled “The Scope of Social Anthropology.” But he was not happy away from Cambridge and his library. And although he gave the Gifford lectures in 1924 and 1925, he did not like lecturing, any form of teaching, or even controversial discussion with professional anthropologists.

Frazer made no original observations in anthropology and is widely criticized for having little or no direct contact with the “savages” he wrote about. Lienhardt attributes some of his popular success to the simplifications encouraged by lack of personal experience. His method was to read the published literature, often for twelve to fifteen hours a day, and to make notes which he later classified, assembled in groups showing the relationships of practices from different parts of the world, and discussed. Leach has shown that his desire to present an elegant prose sometimes led him to distort the original report. Frazer also corresponded with fieldworkers, who valued his stimulating questions and comments, as shown by Bronislaw Malinowski and Sir Baldwin Spencer’s Scientific Correspondence. He compiled a list of questions for fieldworkers, with advice on collecting data, clearly aimed at the amateur, which was published first in 1887 and in its final form in 1907. Many of his correspondents were missionaries and administrators, and although he collected a large number of letters, now at Trinity College, he rarely cited information from them.

The development of Frazer’s work shows both the strengths and the weaknesses of the inductive method. No one before or since has brought together such a volume of data on customs and beliefs, classified and documented to stimulate other workers; yet most of his theories, arising from cogitation in a library on secondhand data, have been modified or superseded, particularly his conception of the evolutionary succession of magic, religion, and science in culture. His analysis of magic into sympathetic and contagious types still has some validity, and Frazer himself never maintained that his own theories were more than transitory and propounded to be superseded. He also believed that if his writings survived, it would be less for the sake of the theories they propound than for the sake of the facts they record.

Although Frazer was unwilling to meet or discuss with anthropologists who did not agree with him, a generation of fieldworkers, of whom Malinowski is probably the best-known, were drawn to the subject by his inspiration, and it developed quickly. His other main importance in his time was simply the popularization of comparative anthropology and the beginning of acceptance of his thesis that mankind is one and that when all is said and done our resemblances to the savage are still far more numerous than our differences from him. The prose style, consciously modeled on that of the eighteenth century, was attractive enough to be widely read, and his demonstration of numerous myths strikingly similar to the Christian stories undermined some conventional religious beliefs.

James Frazer is considered one of the founding fathers of modern anthropology. He was also influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion. His most famous work, The Golden Bough, documents and details the similarities among magical and religious beliefs around the globe. He was knighted in 1914, and there was established a public lectureship in social anthropology at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford, Glasgow, and Liverpool in his honour in 1921.

Among the most influential elements of The Golden Bough is Frazer's theory of cultural evolution. This theory was not absolute and could reverse, but sought to broadly describe three spheres through which cultures were thought to pass over time. Frazer believed that, over time, culture passed through three stages, moving from magic, to religion, to science. Frazer's classification notably diverged from earlier anthropological descriptions of cultural evolution, including that of Auguste Comte, because he claimed magic was both initially separate from religion and invariably preceded religion. He also defined magic separately from belief in the supernatural and superstition, presenting an ultimately ambivalent view of its place in culture. Frazer believed that magic and science were similar because both shared an emphasis on experimentation and practicality. His emphasis on this relationship is so broad that almost any disproven scientific hypothesis technically constitutes magic under his system.

Frazer was a fellow of the Royal Society of London, the Royal Society of Edinburgh and of the British Academy.

Physical Characteristics: Frazer was severely visually impaired from 1930 on.

Doctor

Sir