Lester Willis Young was one of jazz's premier stylists, a startlingly innovative tenor saxophonist whose approach was marked by finesse and relaxation rather than power and passion. On and off the bandstand, Lester "Prez" (for "President") Young was unique.

Background

Lester Willis Young was born on August 27, 1909, in Woodville, Mississippi, and shortly after his birth the family moved to Algiers, Louisiana, just across the river from New Orleans. The father, Willis H. Young, who had studied at Tuskegee Institute, musically tutored Lester, Lester's brother Lee (later a professional jazz drummer), and their sister Irma.

Education

Lester was taught trumpet, alto saxophone, violin, and drums.

Career

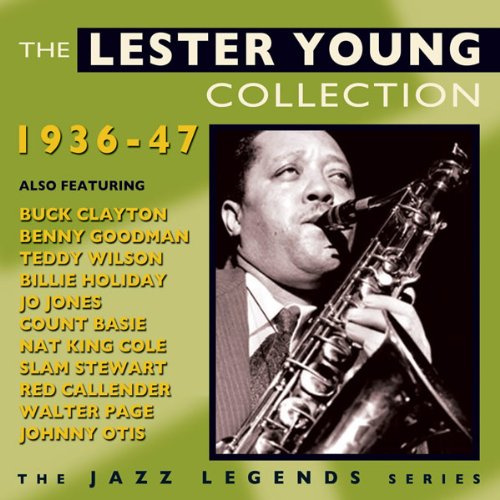

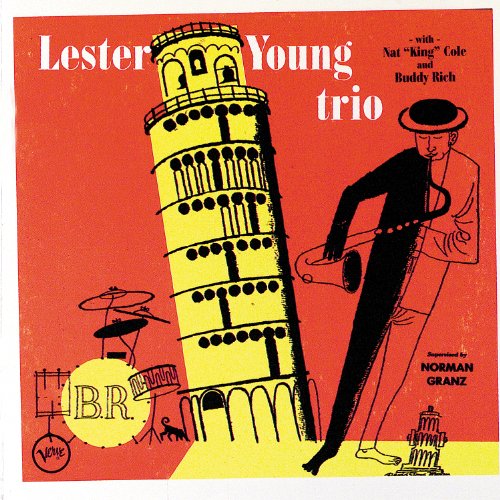

Young's parents divorced in 1919, and the father moved with the children to Minneapolis in 1920; there he married a woman saxophonist and formed a family band, in which Young played alto sax and drums as the band toured the larger Midwestern cities. But Young, unwilling to tour the South, left the band in 1927. For the next five years he worked with a variety of Midwestern bands, including the Original Blue Devils and King Oliver's Band. In 1934 he replaced Coleman Hawkins, the reigning tenor saxophone king, with the famous Fletcher Henderson band, but his lightness of tone on the instrument was ridiculed as "wrong" by the band's other musicians, and after a few months the sensitive Young quit the band. Joins Count Basie Band In 1936 Young petitioned Count Basie for a place in his band and was hired; his early recordings with a small Basie unit as well as with the full orchestra provided Lester with solo spots on "Lady Be Good, " "Shoe Shine Boy, " and "Taxi War Dance" and heralded the arrival of a distinctively new instrumental voice. The band's other superb tenor saxophonist, Herschel Evans, had a heavier, Coleman Hawkins-influenced approach to the instrument, and the contrast produced a friendly rivalry between the two that generated tremendous excitement for audience and record buyers. Evans' death (of heart disease) in 1939 depressed Young severely and was an important reason for his leaving Basie in 1940. For the next several years Young worked as a "single, " playing on both coasts but living chiefly in California. He was now a star, but was drinking heavily and his morale was low, a condition that was ameliorated in 1944 by his rejoining Basie's band. Shortly thereafter, however, he was ambushed one night by an FBI man posing as a jazz fan, who arranged an Army induction for Young on the following day. He was immediately inducted despite his obvious unsuitability for military service: he was a chronic alcoholic and a long-time marijuana smoker, was pathologically afraid of needles, and had tested positive for syphilis. Stationed in Alabama, he was plagued by racism, and he was not allowed to play music (his horn was confiscated), which exacerbated his need for alcohol and narcotic pills. Shortly into his service, pills were found in his possession, and a court-martial resulted in dishonorable discharge, but the Alabama military court prolonged his agony by committing him to a year of hard labor at Fort Gordon, Georgia. The profound effects of this disastrous experience were not immediately apparent. Young returned to civilian life in the midst of a jazz revolution called bebop; he participated in Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP), a concert tour that mixed the young rebels with the Old Guard players, and Young fared better at these concerts than his great rival Coleman Hawkins. His style was more adaptive to the new harmonics-in fact, he had been a primary inspiration for the new music. The sadness that had begun to enter Young's playing, however, is evident on a 1952 recording session with the Oscar Peterson Quartet, although his melodic inventiveness compensates somewhat for the loss of power. Further signs of a crushed spirit gradually emerged, and the 1950s was not a productive decade for Young. Symbolic of the decline, perhaps, was the quirky angle at which Young held his horn while playing: earlier it had been a 45 degree angle, but by the 1950s the rakish tilt had vanished. Always a shy, sensitive man, Young was unable to rebound from the brutal humiliation officialdom had inflicted upon him; his playing in those final years, despite bursts of brilliance, seemed to lack conviction and grew increasingly mechanical and spiritless. In the last dozen years of his life Young had long spells of poor health, undergoing hospital treatment on four separate occasions-in 1947, in 1955, in 1957, and in 1958. Finally, that year, he moved into New York's Alvin Hotel, leaving his wife and son in their home in Queens, New York. A day after returning from a one-month Paris engagement, on March 15, 1959, he died at the hotel of a heart attack brought on by esophageal varicosity and severe internal bleeding. The Young Music When Young arrived on the major jazz scene in the mid-1930s the commanding presence of Coleman Hawkins dictated tenor saxophone style. Hawkins played with fierce intensity, investing every chorus (virtually every bar) with power and passion-the quintessential romantic. Young, on the other hand, was all light and air, velvety of tone, buoyantly disregarding bar lines, floating the rhythm effortlessly, attacking the melody obliquely, subtly rather than head-on. The difference between the two sensibilities is voluminously documented, but nowhere more clearly than on the original 1937 recording of Basie's theme, "One O'Clock Jump, " on which Herschel Evans, a Hawkins disciple, leads off with a thrilling, hard-edged chorus and Lester later responds with an equally thrilling, marshmallow-toned solo. Thus was the Hawkins monolith toppled and replaced by the twin towers of Hawkins and Young-the two essential styles of jazz performance, hot and cool. Examples of Young's genius abound. One of the earliest was a 1935 series of Billie Holiday sessions on which she's accompanied by a Teddy Wilson-led unit; it remains a classic record date, not only for Billie's excellence and the uniformly high quality of the musicianship, but also for the extraordinary musical understanding between Young and Billie, a model of symbiosis. The two sustained a 25-year friendship (she labeled him "the President" or "Prez"; he dubbed her "Lady Day"-nicknames that have endured), and ironically they died the same year. From 1935 to 1946 Young was unfailingly at the top of his form; among his many sterling features with Basie were "Louisiana, " "Easy Does It, " "Every Tub, " "Broadway, " "Lester Leaps in, " "Jumpin' at the Woodside, " "Dickie's Dream, " "I Never Knew, " and his own composition, "Tickle Toe. " His excellent work on clarinet, in evidence on a number of small Basie units (the Kansas City 5), can also be heard in the big band context of Basie's classic "Blue and Sentimental. " Even more noteworthy were his small group tenor saxophone outings of the early-mid-1940s, because those smaller units allowed more "stretching out" (that is, longer solos); a 1942 trio session with pianist Nat Cole and bassist Red Callender produced masterful versions of "Tea for Two, " "Indiana, " "I Can't Get Started, " and the ballad apotheosized by Coleman Hawkins, "Body and Soul. " Lester Young:The Complete Savoy Recordings includes perhaps a half dozen masterpieces: "Blue Lester, " "These Foolish Things, " and two versions each of "Indiana" and "Ghost of a Chance. " A 1945 session with trombonist Vic Dickenson and a rhythm section anchored by pianist Dodo Marmarosa has two astounding tracks, "D. B. Blues" and another version of "These Foolish Things. " Young's greatest recorded live performance is probably the 1946 JATP concert, at which he was co-featured with bebop genius Charlie Parker; his long solos on "Lady Be Good" and "After You've Gone" are a perfect meld of high excitement and artistic integrity. In the 1970s some West Coast jazzmen formed a midsized band (variably eight or nine pieces) called Prez Conference, the sole purpose of which was to perform in full ensemble transcriptions of Young's great solos.