Background

Louis François Élisabeth Ramond de Carbonnières was born on January 4, 1755, in Strasbourg, France, the son of a state official in Alsace Pierre-Bernard Ramond (1715–1796), treasurer of war, and Rosalie-Reine Eisentrand (1732–1762).

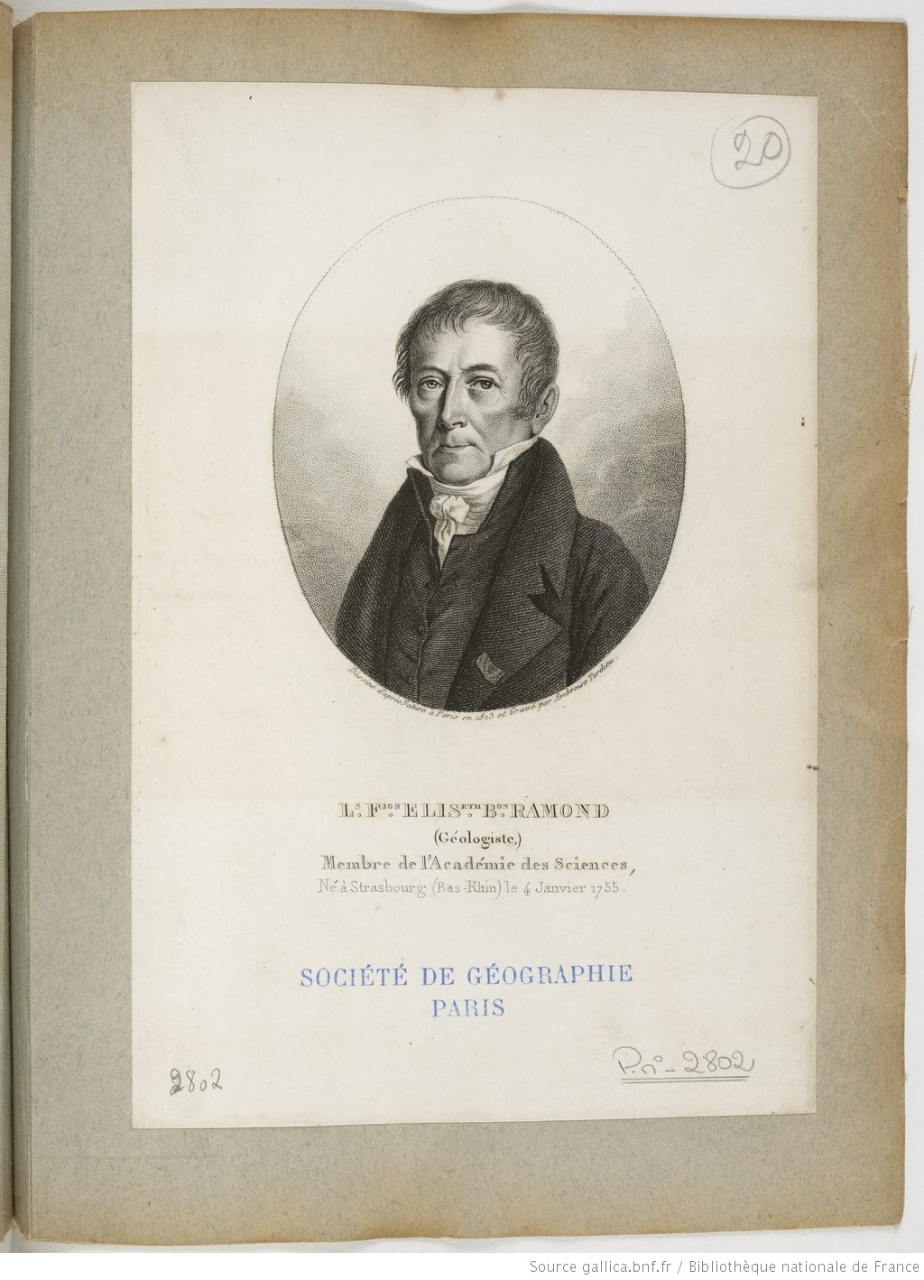

An engraving representing a portrait of L.F. Elis. Ramond.

University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, Alsace, France

Ramond took courses in law and medicine attending the University of Strasbourg in 1775.

Louis François Élisabeth Ramond, baron de Carbonnières, a French politician, geologist, and botanist.

https://www.amazon.com/constitutionnelles-caract%C3%A8res-distinctifs-stabilit%C3%A9-solennelle/dp/B07R1YLYPR/?tag=2022091-20

1789

https://www.amazon.com/barom%C3%A9trique-dispositions-latmosphAre-instruction-%C3%A9l%C3%A9mentaire/dp/B07QXXGHXD/?tag=2022091-20

1811

Botanist geologist politician scientist

Louis François Élisabeth Ramond de Carbonnières was born on January 4, 1755, in Strasbourg, France, the son of a state official in Alsace Pierre-Bernard Ramond (1715–1796), treasurer of war, and Rosalie-Reine Eisentrand (1732–1762).

Ramond took courses in law and medicine attending the University of Strasbourg in 1775.

In 1777 Ramond visited Switzerland, where he met Voltaire, Haller, and Johann Lavater. He also traveled across the Alps in order to study their natural history. In 1776 the Englishman William Coxe had made similar journeys, and his observations were later published as Sketches of the Natural, Civil and Political State of Swisserland in a Series of Letters to William Melmoth (London, 1779). Ramond translated this work into French, adding notes based on his own observations in Switzerland, in particular giving details about the glaciers.

The success of this book, which was published in 1781, attracted the attention of Cardinal Louis de Rohan, and he engaged Ramond as his confidential secretary. In this capacity, Ramond acted as go-between in Rohan's dealings with the notorious charlatan Cagliostro.

In 1787 he accompanied Rohan to Bareges, a small spa in the foothills of the Pyrenees. The mineralogical and botanical observations he made in the neighboring mountains were published in 1789 as Observations faites dans les Pyrenees, a work which aroused great interest. Ramond described glaciers in the Pyrenees which were quite unknown to the scientific world. He also gave an account of the fauna and flora and described the changes that took place in the vegetation with increasing altitude.

During the early years of the Revolution Ramond was in Paris and in 1791 was elected to the Legislative Assembly as a deputy. In debates he supported Lafayette and after the events of 10 August 1792 found it necessary to leave the city immediately. He returned to Bareges, but in 1794 was imprisoned in Tarbes (Hautes-Pyrenees) for ten months because of his political views. After his release, he was appointed a professor of natural history at Tarbes.

In the summer of 1797 Ramond attempted to reach the summit of Mont-Perdu (now Monte Perdido, in Spain) in the central Pyrenees, which he erroneously believed to be the highest peak of the range. He was accompanied by Philippe Picot de la Peyrouse, botanist and inspector of mines, from Toulouse, and several students. The summit was not reached, but the party made the unexpected discovery of abundant fossil remains of marine shells in the limestone strata at an altitude of about 10,000 feet. Ramond and Picot de la Peyrouse, each anxious to claim credit for this discovery, sent separate accounts to the Institut National des Sciences et des Arts (the former Academie des Sciences) in Paris and these were published in the Journal des Mines, 8 (1798).

Ramond continued his researches, botanical as well as geological, in the Pyrenees. In 1800 he returned to Paris and was elected to the Corps Legislatif. He published a new account of his several journeys in the Pyrenees in Voyages au Mont-Perdu et dans la partie adjacente des Hautes-Pyrenees (Paris, 1801). He continued to visit the district and on 10 August 1802 at last succeeded in reaching the summit of Monte Perdido, an altitude of 10,997 feet.

Ramond was elected a member of the Institut National in 1802, and in 1806 Napoleon appointed him prefect of Puy-de-Dome. In Auvergne, he continued to pursue his botanical and geological researches, and barometric measurements also engaged his attention. During the invasion of France in 1814, his house in Paris was ransacked by Cossacks, and manuscripts that he was preparing for publication were destroyed.

Ramond’s major achievement was in his researches of the Pyrenees in terms of its geology and botany. His discovery of abundant fossils in calcareous sediments at a great altitude was undoubtedly a momentous one. At that time it was widely thought that the highest mountains were composed of granite, “the oldest work of the sea,” and other “primitive" rocks; against them lay steeply inclined non-fossil-iferous bedded rocks, chemically deposited or derived by erosion from the primitive mountains. Fossiliferous sediments, horizontally bedded or gently inclined, were believed to be confined to a lower level. Thus, Ramond’s discovery was a revolutionary one, which required new explanations of geological structures. In his Voyages (1801) he also described granites, some of which he thought were less ancient than others, although he did not accept an igneous origin for them.

He was granted the title of baron d'Empire in December 1809. His name is commemorated by the genus Ramonda, beautiful little rock plants named after him. The Soum de Ramond (3,263 m) (known in Spanish as Pico Añisclo) in the Monte Perdido massif is named in his honor. His name is also given to Pic Ramougn (3,011 m), a steep, rocky peak in the Néouvielle massif. Bory de Saint Vincent gave Ramond's name to a chain of craters (Puy Ramond) on the Piton de la Fournaise in Réunion: they are regularly visited by walkers on the GR route which crosses Réunion from north to south, and by the thousands of runners who take part in the Diagonale des Fous each year. The Société Ramond (Ramond Society) was formed in 1865 in Bagnères-de-Bigorre, by Henry Russell (1834–1909), Émilien Frossard (1829–1898), Charles Packe (1826–1896) and Farnham Maxwell-Lyte. It wanted to distinguish itself from traditional academic societies, while still being devoted primarily to the scientific and ethnographic study of the Pyrenees and to the dissemination of knowledge. Ramond, who had excelled in these disciplines, was the best symbol for the new society. The Ramond Society still publishes an annual bulletin. Ramond's herbarium can be seen at the Muséum de l'histoire naturelle in Bagnères-de-Bigorre.

Ramonda pyrenaica in the family Gesneriaceae (a remnant of the flora of the Tertiary) was dedicated to him by the botanist Jean Michel Claude Richard (1787–1868). It grows between an elevation of 1,200 m and 2,500 m in the cracks of schist rocks. There are two other species in the genus Ramonda, R. nathaliae and R. serbica, both of which are found in the Balkans; the genus is the only one in the Gesneriaceae found outside the tropics or the sub-tropics.

Ramond was active in the political life of the country, and from 1800 to 1806, he worked with the Parliament. Also, as a friend of Napoleon, Ramond was named vice-president of the Corps législatif and was a member of the Constitutional Council.

Ramond became a member of the French Academy of Sciences in January 1802. He was also a member of the Société des observateurs de l'homme, which rendered in English as Society of Observers of Man, was a French learned society founded in Paris in 1799.

Ramond married Bonne-Olympe in 1805, widow of General Louis-Nicolas Chérin and the daughter of his friend Bon-Joseph Dacier (1742–1833).

1715–1796

1732–1762

20 October 1744 – 18 October 1818, he accompanied Ramond to Mont-Perdu (now Monte Perdido, in Spain) in the central Pyrenees.

27 March 1776 – 12 September 1854, he accompanied Ramond in his journey to the central Pyrenees in 1797.