Background

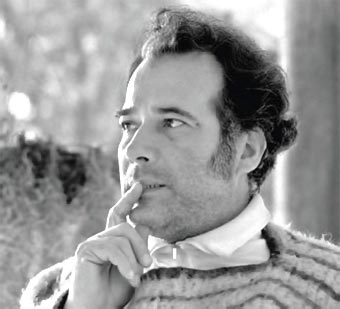

Manuel Mejía Vallejo was born on April 23, 1923 in Jericó, Antioquia, Colombia to Manuel Mejia, a landowner, and Roxana Vallejo, a ceramic artist.

For a time he attended the Universidad de Boliviariana, but his father suffered some financial setbacks and Mejia Vallejo then dropped out of school.

Manuel Mejía Vallejo was born on April 23, 1923 in Jericó, Antioquia, Colombia to Manuel Mejia, a landowner, and Roxana Vallejo, a ceramic artist.

As a child Manuel attended a school his father funded, located on the family's estate; he was then sent to Medellin for high school. For a time he attended the Universidad de Boliviariana, but his father suffered some financial setbacks and Mejia Vallejo then dropped out of school.

One day, after a visit to the cinema, Manuel bought a notebook and began writing La tierra eramos nosotros ("We Were the Land"). The work is deeply evocative of the Antioquia of his childhood, the pastoral estate life that had only recently come to an end for his family. It tracks the visit of a man returning to his former home in the country and contrasts it with his life in the city; nearly all of the names used actually belonged to the people who worked for Mejia Vallejo's father.

Mejia Vallejo's mother, a gifted ceramic artist, was firmly convinced of her son's literary talents and paid the costs for the 1945 publication of La tierra eramos nosotros. Remarkably, although the 229-page novel was literally the first thing Mejia Vallejo had ever written, it caused a sensation. He was praised as an outstanding new voice in Colombian literature. But the country itself was experiencing political and economic crises at the time, and the 1948 assassination of a presidential candidate caused massive riots in Bogota and launched a decade of civil war in which as many as 200,000 Colombians lost their lives. This dismal period is called La Violencia (The Violence), and many writers, artists, and intellectuals fled the country. A military dictatorship from 1953 to 1957 imposed a regime of harsh reprisals and censorship.

During these years Mejia Vallejo worked in Venezuela as a newspaper reporter; he also says he survived on his poker winnings for a time. In the city of Maracaibo he began writing short stories, and in 1951 he earned honors in a Venezuelan national short-story contest for "El Milagro" ("The Miracle") and "La guitarra" ("The Guitar"). He continued to write when he moved to Costa Rica in 1952 and then to Guatemala a year or so later. The fall of Colombia's military dictatorship in 1957 opened new doors for Mejia Vallejo and other exiled writers, and he made plans to return. That same year his collection of short stories, Tiempo de sequia ("Time of Drought"), was published and earned him critical accolades. Many of its stories are concerned with rural Colombian life, and its title story deals with a segment of the population who live in abject poverty. Another Tiempo de sequia piece, "Al pie de la ciudad," soon evolved into a 1958 novel of the same title; its characters live in the Los Barrancos neighborhood of Medellin, at the "foot" of the city.

Tiempo de sequia marked Mejia Vallejo's beginning as a serious participant in the Colombian literary scene, though its publication had come a dozen years after La tierra eramos nosotros. His second full-length novel, Al pie de la ciudad, won the contest of a renowned Buenos Aires publisher and was met with critical acclaim soon afterward. First told from viewpoint of young boy growing up in this barrio of Medellin, Al pie de la ciudad charts the history and changes of the unique neighborhood of Los Barrancos; an affluent doctor is the main figure in its second part, but the third section fuses both narrative focal points.

Upon returning to Colombia around 1958. Mejia Vallejo was offered a post as director of Imprenta Departamental, an important publishing house in Medellin. From this position he launched the series "Coleccion de Autores Antioquenos," featuring writers from his native region; the selection became rather controversial among the greater Colombian literary establishment and debates raged in the press regarding the editors' choice of writers.

Raymond Leslie Williams, writing in Dictionary of Literary Biography, termed both Al pie de la ciudad and Mejia Vallejo's next work, El dia senalado ("The Special Day"), "early contributions to the modern novel in Spanish America... His modern narrative techniques involve the innovative use of narrators and structures." Published in 1964, El dia senalado was a great commercial and critical success for the writer. Set in the isolated town of Tambo in Antioquia between 1936 and 1960, the story is told from two different perspectives - that of a young boy growing up in the region and that of a grown man returning to extract revenge upon his long-lost father - but their stories later merge. The horrors of La Violencia figure largely in the narrative, and the character of the village priest, a simple and good man with great faith in humanity, also plays an important role. In the end, the son discovers that his father is the leader of the guerrilla group battling the Colombian army and does not kill him; by this time the younger man has already fathered a child with a prostitute and then left it behind as his progenitor had done.

By the mid-1960s Mejia Vallejo had abandoned his publishing job and began a venture with other writers to promote Antioquian literature. They called their group Papel Sobrante ("Extra Paper"), and sold surplus paper to fund their own publishing ventures. The group included Oscar Hernandez Monsalve, Dario Ruiz Gomez, Dora Ramirez, Antonio Osorio Diaz, John Alvarez Garcia, and Mejia Vallejo. The last of the eight volumes Papel Sobrante issued came in 1967 with Mejia Vallejo's Cuentos de la zona torrida ("Tales of the Torrid Zone").

But 1967 was also an important year for Latin American letters because of the publication of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Cien anos de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude). Hailed as the most important and influential writer Colombia has ever produced, Garcia Marquez used a style that came to be known as magical realism and was soon widely imitated. Mejia Vallejo wrote little over the next few years. "Garcia Marquez's shadow was an insurmountable factor for all other Colombian writers, including Mejia Vallejo," noted Williams in the Dictionary of Literary Biography essay. "He spent his time teaching literature classes at the Universidad Nacional de Medellin and writing on his farm outside the city."

That estate, called Ziruma, which means "heaven" in the indigenous language of Antioquia, was purchased with the savings from his first early successes as a writer. There Mejia Vallejo wrote his next novel, Aire de tango, published in 1973. A homage to the cult of the tango and one of its leading champions, the work is set in the rougher Guayaquil barrio of Medellin.

Aire de tango won a major literary prize in Colombia, the Premio Vivencias, and marked Mejia Vallejo's entry into a canon of seasoned Colombian writers and intellectuals. His next work, Las noches de la vigilia ("Vigilant Nights"), explored new structural territory: the work is a collection of over five dozen brief narratives all set in the small town of Balandu. Two years later Mejia Vallejo published a volume of short love poems, Practicas para el olvido; he then again turned to addressing the wrongs committed in recent Colombian history with the 1979 novel Las muertes ajenas ("Foreign Deaths").

In Tarde de verano ("Summer Afternoon"), Mejia Vallejo's 1980 novel, he borrows a bit from other contemporary Latin American writers. The work, told in a traditional narrative voice, recounts the nevertheless otherworldly occurrences that begin to plague the life of an ordinary couple. In his 1987 work Ui sombra de tu paso ("The Ghost of Your Step"), he revisits the heady days of new intellectual freedom in Colombia and especially Medellin in the early 1960s. A love story, its narrator recounts his relationship with a woman named Claudia in flashback to those days; many leading Colombian literary figures appear in the anecdotes. "A subtle subtext is the story of the protagonist becoming a writer," noted Williams in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. "The formative years narrated in this novel are, in fact, the years during which Mejia Vallejo matured as a writer." Mejia Vallejo's 1988 novel, La casa de las dos palmas ("The House of Two Palms"), again revisited his fictional sleepy town of Balandu, this time in the early years of the twentieth century.

An esteemed figure in Colombian letters, Mejia Vallejo was invited to the presidential palace to speak on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday in 1983.

Vallejo died on July 23, 1998 in El Retiro.

Manuel Mejia Vallejo is one of Colombia's most respected literary names, with over four decades of critically acclaimed work to his credit. Since the publication of his first novel in 1945 at the age of just twenty-one, Mejia Vallejo and his literary efforts have survived political crises, peer-fomented controversy, and the impact of Latin American magical realist literature. As both a writer and a publishing-industry heavyweight, Mejia Vallejo has championed the works of his native region, the Colombian province of Antioquia, of which Medellin is the capital. From Antioquia, long isolated as a valley surrounded by forbidding peaks, arose a sense of separate culture and a rich oral tradition; the area is also the birthplace of several other notable figures in Colombian literary history. Many of Mejia Vallejo's novels and short stories pay homage to Antioquia's rural culture of decades past.

Manuel married Dora Luz Echeverria Ramirez on January 31, 1975.