Martha G. Anderson is an American writer and educator. She works as history professor at Alfred University in New York.

Background

Anderson was born on October 4, 1948, in St. Peter, Minnesota, the daughter of H. Milton Anderson, a college mathematics professor, and Charlotte Loseth, an English teacher and office manager.

As a child, she enjoyed reading about different eras and learning about other cultures. By the age of twelve, she decided to prepare for a career writing historical novels by pursuing dual Ph.D.'s in history and English. She later drifted toward art and found that could combine these interests by specializing in non-Western art history.

Education

Anderson received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Saint Olaf College in 1970. She then graduated from New York University Institute of Fine Arts with a Master of Arts degree in 1976, and Indiana University with a Ph.D. in 1983.

Because studying the art of another culture demands an interdisciplinary approach, she's been influenced by a variety of scholars, including anthropologists, historians, theologians, and linguists.

Career

Anderson, a professor of art history at Alfred University in upstate New York, has concentrated her research on African art, focusing specifically on the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Anderson participated in two prominent exhibitions pertaining to African art, one of which opened in New York and the other in California; the exhibition catalogs for these shows, which she coauthored, were received as valuable contributions to the growing body of literature on African art and anthropology.

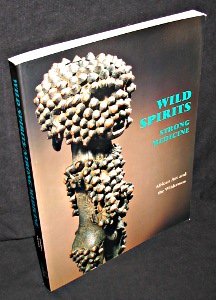

Anderson spent two years in the late 1970's living in the Niger Delta region and researching the nature spirits of the Ijo (pronounced "Ijaw") people. Upon her return to the United States, she began working on her first exhibition catalog: Wild Spirits, Strong Medicine: African Art and the Wilderness, in collaboration with Christine Mullen Kreamer. The exhibition opened in June of 1989, initially presented at the Center for African Art in New York City and making subsequent appearances at four other venues. The exhibition aimed to illuminate the concept of wilderness in African art - not drawing simply from a background of art history, but participating in a broader ethnological discourse.

Anderson and Kreamer's catalog is divided into five chapters, each of which details one theme pertaining to the ways in which African cultures interact with the natural world. The first chapter, entitled "Wilderness," takes an anthropological approach to examining the dichotomy between "civilization" and the "wild" world of nature - a distinction made in varying degrees by many peoples of Africa. The authors discuss boundaries in the second chapter, "Space," examining the ways in which the Wilderness can be used to define the human social realm. "Denizens of the Wild," the next chapter, addresses the religious beings associated with the Wilderness, while also discussing artistic representations of these beings. The fourth chapter, "Diviners, Healers and Hunters," examines the role of these specialists whose activities require them to maintain a relationship with the Wilderness; the final chapter, "Power," deals with that same relationship as held by certain people in positions of power, such as politicians, witches, and kings.

Many critics were impressed with the range and depth of the study, although some felt that the approach was somewhat too broad. In general, however, critics responded favorably to Wild Spirits, Strong Medicine; Peek called it "a valuable introduction to the diversity of African peoples' conceptions of the Wilderness as manifest in their arts," and Choice's C. D. Roy noted that "this is one of the most useful and informative books on African art to appear [recently]."

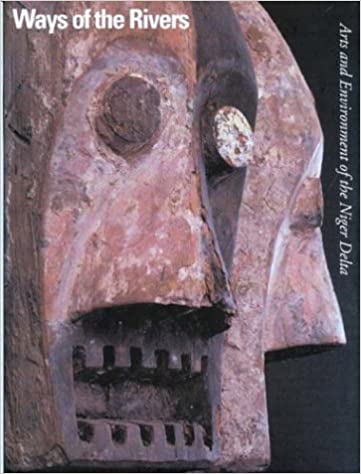

Anderson returned to the Niger Delta region in the early 1990's, this time to study the female diviners of the Ijo who are instrumental in producing many of the culture's noted artistic and performative works: giant wood sculptures and masquerades. This research led Anderson to work on her second exhibition catalog, Ways of the Rivers: Arts and Environment of the Niger Delta (written with Philip M. Peek), which dealt specifically with the Ijo, along with other Delta peoples. The exhibition opened at the UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History before traveling to other venues, and it explored the relationship of the river environment to the arts and rituals of the people. Nancy B. Turner noted in Library Journal that Anderson and Peek's volume "serves as more than an exhibition catalog," and praised its in-depth, anthropological approach. The catalog examined the ways in which the Delta peoples have been dealing with their unique environment - prone to heavy rains, tides, and floods - for hundreds of years. The different ethnic groups of the region, while often separated and isolated by the vast system of rivers and islands that make up the Delta, have also utilized these waterways as a means for transportation. The trading routes that developed as a result were the means for exchanging art forms and ideas not only with other Delta communities but also with Western countries; Anderson and Peek note the frequency with which European influence appears in the art of the Niger Delta. Ways of the Rivers celebrates the vibrant, oversized sculptures and elaborate masquerades that have emerged from the Delta region, exploring in particular two thematic trends: the "water-related" ethos and the "warrior" ethos. The catalog also addresses the recent development of the region, which - oil drilling in particular - threatens the delicate river-based ecosystem. Again, critics were favorably impressed with the scope of the work and treatment of the subject, and a reviewer for Tribal Arts called it "a fine catalogue for a fine exhibition."

Views

Anderson's work typically combines library, museum, archival, and field research. Because fieldwork draws on lived experience, it can take a good deal of time to digest. Winnowing out extraneous information and excessive detail proves to be the most challenging part of the process. Once she's done that, she works on style. She tries to draw readers into the text by establishing and varying the rhythm.

She told: "Although I am concerned with academic integrity, I also desire - and find it morally imperative - to give something back to the Ijo people. In addition to recording what I have learned about their culture, I want to make others care about them and others who live in similar circumstances. Exhibition catalogs provide a good way to do this, because they address a broader audience than the academic press. In order to make my work accessible to non-academics, I try to keep it jargon-free and lively."