Background

Pierre d'Ailly was born in Compiègne, France in 1350, in a prosperous bourgeois family.

Pierre d'Ailly's World Map in his Imago Mundi , 1410. The Seventh Figure from Pierre d'Ailly's Imago Mundi, is a modified Macrobius-type climata map or diagram. The placement of the Ypborei and the Arũphei on two of the quadrants surrounding the North Pole was mimicked by Johannes Ruysch on his map.

Concordantiae astronomiae cum theologia, Augsburg 1490: Theologe und Astronom im Disput.

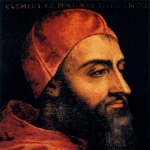

Cardinal Pierre d'Ailly, 1351 – 1420, French theologian, astrologer, and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

Imago mundi (Reproduction), Pierre d'Ailly.

Folio from Pierre D'Ailly's 'Imago Mundi' by Spanish School : 24x18in.

Pierre d'Ailly's World Map in his Imago Mundi , 1410. The Seventh Figure from Pierre d'Ailly's Imago Mundi, is a modified Macrobius-type climata map or diagram. The placement of the Ypborei and the Arũphei on two of the quadrants surrounding the North Pole was mimicked by Johannes Ruysch on his map.

In 1410, a cardinal and chancellor of France, Pierre d'Ailly, published a map, the Imago Mundi, which represented Africa.

The University of Paris where Pierre d'Ailly received his doctorate of theology in 1381.

The College of Navarre (French: Collège de Navarre) was one of the colleges of the historic University of Paris, rivaling the Sorbonne and renowned for its library.

cardinal theologian astrologer scholars cosmography

Pierre d'Ailly was born in Compiègne, France in 1350, in a prosperous bourgeois family.

D’Ailly studied at the College of Navarre of the University of Paris, where he received his doctorate of theology in 1381.

Pierre d'Ailly was grand master of Navarre front 1384 to 1389, and from 1389 to 1395 he was chancellor of the University of Paris. In 1395 d’Ailly became bishop of LePuy, and in 1397 bishop of Cambrai. He was made a cardinal in 1411. D’Ailly wrote commentaries on Aristotle (the De anima and the Meteorológica), as well as a number of astronomical and astrological works, including a commentary on the De sphaera of Sacrobosco. In his treatises on astrology, he reflects a more lenient attitude than that of either Nicole Oresme or Henry of Hesse. He was also concerned with the problem of calendar reform, and wrote a work on this subject for the Council of Constance (1414). After the council, d'Ailly returned to Paris. When in France's civil discord the Burgundian faction seized Paris in 1419, killing some professors in the process, he fled south and retired to Avignon. D'Ailly, known as the Cardinal of Cambrai, died in 1420 in Avignon.

Pierre d'Ailly`s most significant scientific work is a collection of cosmographical and astronomical treatises with the collective title Imago mundi. The Imago includes sixteen treatises on geography and astronomy, and the concordance of astrology, astronomy, and theology with historical events; only the first of these is the Imago mundi properly speaking. In the geographical portion of the Imago (the first treatise), d’Ailly makes use of the newly translated Geography of Ptolemy.

He was an advocate of the calendar reform later made by Pope Gregory XII; and, like many important thinkers of his day, he took great interest in astrology, which he felt was consistent with religion. His book on geography, Imago mundi, was read carefully by Columbus, who said that it inspired his voyage of 1492 by suggesting the feasibility of sailing from Spain west to India. D'Ailly also wrote on astronomy, meteorology, mathematics, logic, metaphysics, and psychology.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

In his religious affiliation Pierre d'Ailly was a Roman Catholic and was one of the most formidable adversaries of John XXIII at the Council of Constance (1414–1418). His works on the nature of the Church had the most lasting influence. He developed the theory of conciliarism and the concept that the only infallible body in the Church is the whole of the faithful. These ideas were later shared by the Protestant reformers.

In his philosophical and scientific outlook, d’Ailly is considered a nominalist; however, his scientific writing shows little originality and much unacknowledged borrowing. He has a more significant claim to historical prominence as a leader of the conciliar movement. He advocated the doctrine of conciliarism - the subordination of the pope to a general council - and in 1381 he suggested convoking such a council in an effort to end the schism.

One of the university's chief concerns was the Western Schism (1378-1417), in which rival popes claimed legitimacy. At first D'Ailly supported the Avignon pope Benedict XIII, but he soon became a radical leader of the Conciliar movement. The Conciliarists argued that a general council of the Church is superior to the pope and that therefore a general council could end the schism by choosing a new pope satisfactory to all parties. D'Ailly played a prominent part at the Council of Pisa (1409), which elected a new pope, Alexander V. In 1411 Alexander's successor, John XXIII, made D'Ailly a cardinal. When the rival popes refused to resign, however, the Council of Constance (1414-1418) was called. D'Ailly was an acknowledged leader and effected the decision to have the contending popes abdicate. The council then elected a new pope, Martin V, and the schism was ended. D'Ailly himself was a candidate for the papal throne, but he lost the election because of opposition from France's enemies, England and Burgundy. He retired for safety to Avignon, where he served Martin V.

Quotations: “The power of harmonies raptures the human soul so much to itself that it is not only elevated above other passions and cares, but even above itself.”

In the spring of 1379 Pierre d'Ailly, in anticipation even of the decision of the University of Paris, had carried to the pope of Avignon, Clement VII the "role" of the French nation, but notwithstanding this prompt adhesion he was firm in his desire to put an end to the schism, and when, on the 20th of May 1381, the university decreed that the best means to this end was to try to gather together a general council, Pierre d'Ailly supported this motion before the king's council in the presence of the duke of Anjou.

Baldassarre Cossa (c. 1370 – 22 December 1419) was Pisan antipope John XXIII (1410–1415) during the Western Schism. The Catholic Church regards him as an antipope, as he opposed Pope Gregory XII whom the Catholic Church now recognizes as the rightful successor of Saint Peter. He was eventually deposed and tried for various crimes, though later accounts question the veracity of those accusations.

He raised Pierre d'Ailly to the rank of cardinal (June 6, 1411), and further, to indemnify him for the loss of the bishopric of Cambrai, conferred upon him the administration of that of Limoges (November 3, 1412), which was shortly after exchanged for the bishopric of Orange. He also nominated Pierre d'Ailly as his legate in Germany (March 18, 1413).