Background

Robert Sidney Maestri was born on December 11, 1899, in New Orleans. He was the son of Francis Maestri and Angele Lacabe.

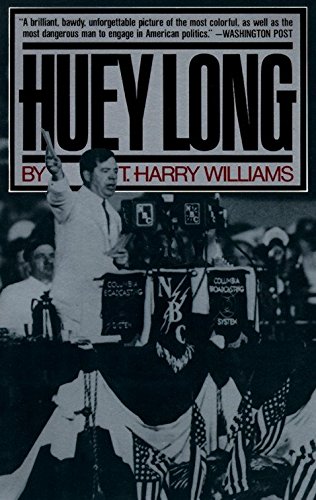

(Winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award,...)

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, this work describes the life of one of the most extraordinary figures in American political history. Huey Long was a great natural politician who looked, and often seemed to behave, like a caricature of the red-neck Southern politico, and yet had become at the time of his assassination a serious rival to Franklin D. Roosevelt for the Presidency. In this "masterpiece of American biography" New York Times Book Review, Huey Long stands wholly revealed, analyzed, and understood.

https://www.amazon.com/Huey-Long-T-Harry-Williams/dp/0394747909?SubscriptionId=AKIAJRRWTH346WSPOAFQ&tag=prabook-20&linkCode=sp1&camp=2025&creative=165953&creativeASIN=0394747909

Robert Sidney Maestri was born on December 11, 1899, in New Orleans. He was the son of Francis Maestri and Angele Lacabe.

Maestri attended public and parochial elementary schools but left school after the third grade to work in the family furniture business. He also took courses at a local business school.

Possessed of a keen business sense, Maestri eventually took over the firm and added real estate and securities to his rapidly expanding financial interests. During the early 1920's, Maestri tried to curry favor with the New Orleans Regular Democratic Organization (RDO), the local political machine, but it failed to satisfy his political ambitions. So in 1927, Maestri hitched his political fortunes to the rising star of Huey Pierce Long.

Maestri, by exhibiting total loyalty and exceptional fund-raising ability, quickly assumed a privileged position within the Long inner circle.

In 1929, he helped Huey Long stave off impeachment proceedings with sizable and timely financial contributions to Long's camp, who distributed the money wisely.

In 1936, the year after Long's assassination, a struggle between the Long machine and the RDO led to the forced resignation of New Orleans mayor T. Semmes Walmsley. Maestri, now a major force in the state Democratic party organization, became the Longite choice for the office. He ran unopposed and immediately asserted powerful influence with both political groups.

A state legislature compliant to the Long organization extended his mayoral term to 1942. The new municipal chief executive took his post seriously. Maestri moved swiftly to rejuvenate and revamp the Crescent City's pitiful fiscal structure, a casualty of the lengthy feud between Walmsley, who headed the RDO, and the vindictive Long organization.

Maestri maintained close ties with Longite Louisiana governor Richard Leche and used the financial support of the state administration to benefit the city. He also successfully tapped New Deal funds to finance municipal building projects. During a visit by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to New Orleans in April 1937, Maestri experienced an unfortunate and mercifully brief brush with the national media.

While Roosevelt dined on Oysters Rockefeller in Antoine's Restaurant in the French Quarter, the earthy host mayor blurted out, "How ya like dem ersters?" His comment drew nationwide attention and became a Crescent City legend.

In 1939, he was a major figure in the "hot oil" scandals that rocked Louisiana, although he himself evaded conviction. Labor interests also suffered. Maestri also resisted Governor Sam Houston Jones's efforts to introduce a civil service system and voting machines to New Orleans, reforms that would have threatened his power and the influence of the urban machine.

In 1942, Maestri nonetheless easily won re-election over attorneys Herve Racivitch and Shirley Wimberly. In his second term, however, the positive aspects of his administration dissipated. Maestri stopped his daily tours of the city, met less frequently with citizens, and devoted more time to political maneuvering. Municipal building projects stalled.

Many attributed the change to Maestri's differences with Governor Jones, a leader of the anti-Long faction in state politics, and the mayor's growing penchant for political manipulation. Others noted the demands that World War II placed upon municipal resources. Still, others contended that Maestri had simply lost interest in the city government.

In late 1945, an internal dispute between the Louisiana Democratic Association and the RDO further weakened Maestri's political position. On January 22, 1946, deLesseps Story Morrison, a youthful war veteran and state legislator, defeated Maestri in a close mayoral election. When the RDO reorganized after the election, it had no place for the former mayor.

In 1950, Maestri indicated a desire to run again for mayor. When he received no backing from either Governor Earl Long, a former ally, or the RDO, he withdrew from the mayoral race and retired from politics.

For the remainder of his life, Maestri lived in the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans, managed his vast financial interests, and occasionally engaged in quiet political maneuvering.

Maestri died in the Crescent City, the source of his wealth and the seat of his political power.

Maestri provided major financial backing for Long's victorious gubernatorial campaign in 1928. He became a leader of the Louisiana Democratic Association, Long's political organization, and served admirably as Louisiana Conservation Commissioner from 1929 until 1936. Through a system of tax reform, scavenging, and the cajoling of local business leaders, within two years the mayor established financial stability in a city that had been virtually bankrupt. Despite his coarse demeanor and lack of formal education, the mayor excelled at head-to-head negotiations.

(Winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award,...)

Unsubstantiated rumors that Maestri repeatedly denied linked him to local prostitution and gambling operations. During World War I, he served in the U. S. Army. Maestri became a wealthy man whose ambition drove him to seek political office. However, his blunt manner and laconic way of speaking seemingly stood in the way of political success.

Despite his lack of sophistication and blunt retorts, Maestri was a warm man who cared about his constituents. He personally toured the city each day to look for municipal problems and to develop work assignments for repair crews. He also met regularly with citizens to hear their grievances.

He was a generous man who often helped those in need with gifts of money from his own pocket. He also possessed a sharp sense of humor. When associates advised him to respond to a critical newspaper story, Maestri replied, "How can I fight the newspapers? I buy ink by the bottle; the newspapers buy it by the carload. "

With his family, Maestri enjoyed weekends and vacations in the couple's second home in Mandeville, a small community on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain.

There was a dark side to the Maestri administration. The mayor was a classical political boss who ran a powerful spoils machine. Maestri, moreover, did little to control vice and police corruption in the Crescent City. When police officers complained to the mayor about low salaries, Maestri reputedly exclaimed heatedly, "What do you mean you want more money? You have a badge and a gun. If you want more money, go get more money!"

On August 18, 1937, Maestri married Hilda Bertonier, his secretary. They had one daughter, born in 1942.