Background

Thurgood Marshall was born on July 2, 1908, in Baltimore, Maryland, the second son of William Canfield Marshall and Norma Arica Marshall.

Howard University, Washington, D.C., United States

Autherine Lucy in a press conference with Roy Wilkins, Executive Director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), 2 March 1956.

Image result for thurgood marshall supreme court

Premium Photographic Print - NAACP Chief Counsel Thurgood Marshall Standing on Steps of the Supreme Court Building by Hank Walker.

Thurgood Marshall - Thurgood Marshall Photos - African American History Through Photos.

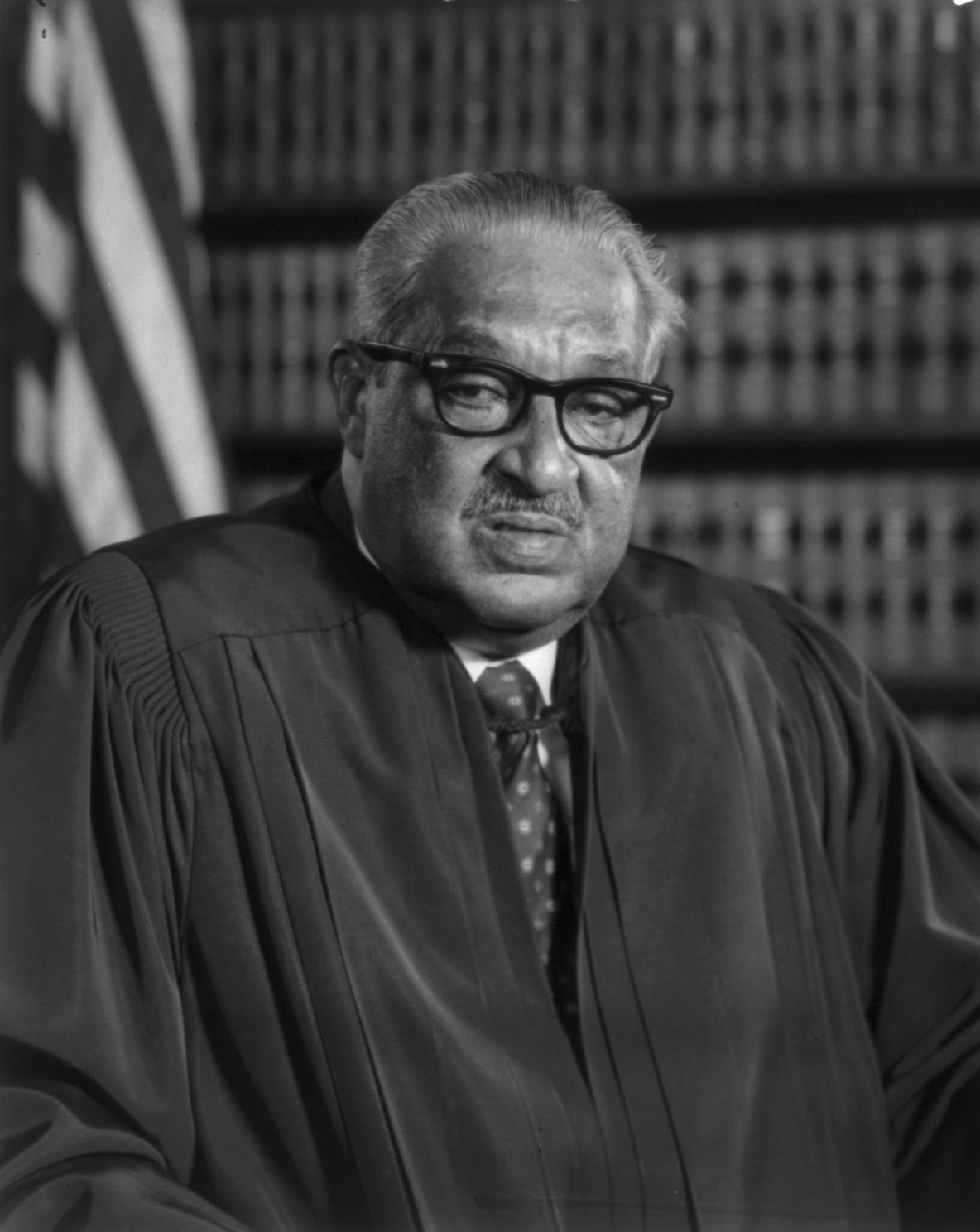

Thurgood Marshall became the first African American Supreme Court justice on August 30th, 1967.

Thurgood Marshall, New York attorney

Thurgood Marshall was born on July 2, 1908, in Baltimore, Maryland, the second son of William Canfield Marshall and Norma Arica Marshall.

Thurgood Marshall graduated from Frederick Dou glass High School in Baltimore in 1925 and then enrolled in Lincoln University in Chester, Pennsylvania, which had been chartered in 1854 as the nation’s first institution of higher learning for blacks. He graduated in 1930. Prevented by his race from attending the University of Maryland School of Law, Marshall pursued a legal education at Howard University instead. He graduated first in his class in 1933, was admitted to the Maryland bar, and began a law practice on his own in Baltimore.

Within a short time, Marshall was handling cases in association with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Perhaps most notable, in 1935 he assisted in pressing legal claims before the Maryland Court of Appeals that forced the University of Maryland School of Law to admit its first African-American student. The following year, Charles Hamilton Houston, who had been vice-dean of the Howard Law School while Marshall had been a student, invited Marshall to join him in New York as special assistant legal counsel to the NAACP. In 1938 Houston resigned as special counsel to the NAACP, and Marshall took his place. He was 30 years old at the time. A year later, the NAACP created the Legal Defense and Educational Fund to wage war against racial segregation and Marshall was chosen to be its director. In this position, he coordinated the litigation strategies that challenged segregation in a series of cases. By 1943 he had begun to press the cause of equal rights before the Supreme Court itself, and in the years that followed, he would serve as an advocate in cases whose holdings inched steadily closer to the dismantling of segregation. In Smith v. All- wright (1944), for example, he helped persuade the Court to declare unconstitutional the “whites-only” Democratic primary in Texas. Six years later he was back before the Court, winning a declaration in Sweatt v. Painter (1950) that Texas’s refusal to admit a black applicant to the University of Texas Law School and its attempt to establish a parallel law school for blacks violated the equal protection clause.

On September 23, 1961, after Marshall had devoted nearly a quarter-century to civil rights litigation, President John F. Kennedy ap-pointed him to sit on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Resistance to the appointment from southern senators delayed Marshall’s confirmation almost a year. But finally, on September 11, 1962, the Senate confirmed his nomination by a vote of 54-16. After Marshall had spent four years on the federal appeals court, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him solicitor general of the U.S. in July 1965. The solicitor general represents the U.S. government in cases before the Supreme Court, and Marshall’s appointment made him the first African American to hold this prestigious post, often a stepping stone to a seat on the Supreme Court itself. In fact, on June 13, 1967, President Johnson nominated Marshall to become an associate justice, replacing Tom C. Clark of Texas, who had retired from the Court after Johnson had made Clark’s son, Ramsey, attorney general. After the Senate confirmed the appointment by a vote of 69-11 on August 30, Marshall became the first African-American justice on the Court.

Marshall retired from the Court on June 27,1991. He was 82 years old at the time, with more than a half-century behind him as the champion of equal rights and civil liberties, first as a lawyer and later as a judge. He lived for another year and a half before dying of heart failure on January 24, 1993, in Washington, D.C., at die age of 84.

Thurgood Marshall was the first African American member of the Supreme Court. As an attorney, he successfully argued before the U.S. Supreme Court the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), which declared unconstitutional racial segregation in American public schools.

Marshall earned an important place in American history on the basis of two accomplishments. First, as legal counsel for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), he guided the litigation that destroyed the legal underpinnings of Jim Crow segregation. Second, as an associate justice of the Supreme Court–the nation’s first black justice–he crafted a distinctive jurisprudence marked by uncompromising liberalism, unusual attentiveness to practical considerations beyond the formalities of law, and an indefatigable willingness to dissent.

With these and many other constitutional triumphs, for which Marshall earned renown as “Mr. Civil Rights,” he eventually pursued the lion of segregation into the den of public education. Finally, in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Marshall coordinated the litigation strategy that insisted on naming segregated public schools inherently unequal. On May 17, 1954, die Supreme Court announced its agreement in the case: that segregation in public schools violated the Constitution’s equal protection guarantee. This ground-breaking ruling eventually spelled the end of government- sanctioned racial segregation not only in public schools but in all public facilities. The following year, however, disappointment followed fast on the heels of this victory. The Supreme Court declined to order immediate integration of previously segregated public school districts, declaring instead that schools had to integrate “with all deliberate speed.” And on a personal level, Marshall’s wife, Vivian, died of cancer in February 1955. At the end of that year, Marshall remarried, and with his new wife, Cecilia Suyat, he had two sons: Thurgood, Jr., and John William.

During the first part of his 24-year career on the Court, Marshall joined the solid liberal majority led by Chief Justice Earl Warren. He thus participated in the later part of the Warren court’s constitutional revolution, which aggressively' championed individual rights and liberties. He wrote, for example, the opinion in Stanley v. Georgia (1969), decided in Warren’s last term as chief justice, which held that states could not punish the private possession of obscene materials in a home. After Earl Warren s departure, however, and his replacement by Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, the Court tilted to a more conservative perspective, and consequently Marshall often found himself in a dissenter’s position in the years that followed. For example, he was part of the majority that temporarily halted capital punishment in the United States in Furman v. Georgia (1972) on the grounds that the death penalty, as then executed by the states, was cruel and unusual. But after states revised their capital punishment schemes and the Supreme Court approved these revisions beginning in Gregg v. Georgia (1976), Marshall joined with William Brennan, Jr., to dissent in every case that upheld the death penalty.

Thurgood Marshall was married to Vivian Burey. His second marriage was to Cecilia Son He had two children, Thurgood and John.

During the 1950s, Thurgood Marshall developed a friendly relationship with J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.