Background

Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby was born on December 28, 1898, in Stockholm, Sweden, the son of Arvid and Alma Charlotta (Marelius) Rossby.

1927

Rossby's meteorology was often intertwined with aviation. Rossby (right) was among the Weather Bureau meteorologists who assisted Navy flyer Richard Byrd prepare for a transatlantic flight in June, 1927. Photograph taken by Fotograms news service; scanned from a print in Roger Turner's personal collection.

1953

Carl-Gustaf Rossby was awarded the Symons Gold Medal, which was established in 1901 in memory of George James Symons, a notable British meteorologist.

Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby, a Swedish-born American meteorologist who first explained the large-scale motions of the atmosphere in terms of fluid mechanics.

Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby, 1898–1957

Carl-Gustaf Rossby, Professor of Meteorology at the University of Stockholm (1947-1957).

Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Rossby entered the University of Stockholm in 1917, and studied mathematics, mechanics, and astronomy.

Carl-Gustaf Rossby was a Professor of Meteorology at the University of Stockholm.

Carl-Gustaf Rossby

Rossby experimented with observing fluid dynamics in a rotating tank during a fellowship at the United States Weather Bureau in 1926-27. (Image via NOAA Photolibrary.)

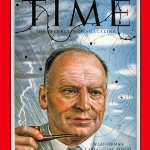

Time used a profile of Carl-Gustaf Rossby to introduce readers to the 1950s advances in atmospheric science, including predicting the weather using digital computers.

American Meteorological Society (AMS), Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Carl-Gustaf Rossby was a member and at some point a President of the American Meteorological Society (1944–45).

University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Saxony, Germany

In 1921 Rossby studied hydrodynamics at the Geophysical Institute of the University of Leipzig.

University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Rossby came into meteorology and oceanography while studying geophysics under Vilhelm Bjerknes at the Geophysical Institute, the University of Bergen in Bergen, Norway during 1919.

meteorologist oceanographer scientist

Carl-Gustaf Arvid Rossby was born on December 28, 1898, in Stockholm, Sweden, the son of Arvid and Alma Charlotta (Marelius) Rossby.

Rossby entered the University of Stockholm in 1917 and studied mathematics, mechanics, and astronomy. Rossby came into meteorology and oceanography while studying geophysics under Vilhelm Bjerknes at the Geophysical Institute, the University of Bergen in Bergen, Norway during 1919, where Bjerknes' group was developing the groundbreaking concepts that became known as the Bergen School of Meteorology, including a theory of the polar front. In 1921 Rossby studied hydrodynamics at the Geophysical Institute of the University of Leipzig. He also continued his studies of mathematical physics at the University of Stockholm and received his licentiate in 1925.

Rossby’s career in meteorology began in 1919 when he joined the scientific staff at the Geophysical Institute at Bergen, Norway. Here the polar-front theory of cyclones was being developed under the leadership of V. F. Bjerknes. In 1921 Rossby studied hydrodynamics at the Geophysical Institute of the University of Leipzig and worked at the Prussian Aerological Observatory at Lindenberg. In the same year, he returned to Stockholm and entered the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Service. He took part in several meteorological and oceanographic expeditions. He also continued his studies of mathematical physics at the University of Stockholm and received his licentiate in 1925.

In 1926 he won a one-year fellowship to the United States Weather Bureau in Washington. He remained in the United States for more than twenty years, obtaining American citizenship in 1939.

Rossby was instrumental in bringing American meteorology to a position of world leadership. At first, however, his attempt to introduce the polar-front theory and other innovations was met with hostility at the United States Weather Bureau, which was largely bureaucratic rather than a center of scientific research. In 1927 Rossby accepted the chairmanship of the Committee on Aeronautical Meteorology of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for Promotion of Aeronautics, in which capacity he established a model weather service for civil aviation in California. He became associate professor of meteorology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1928 and rapidly established a strong department.

Rossby was appointed assistant chief of the Weather Bureau, in charge of research and education, in 1939. During the next two years, he worked at reorganizing the Bureau and strengthening its scientific mission. In 1941 Rossby became chairman of the newly founded department of meteorology at the University of Chicago, where he brought together an outstanding group of scientists from many different countries. During the early 1940’s, when the needs of warfare made meteorology a key science, Rossby organized a very effective military educational program in meteorology and worked for the establishment of an adequate global observing and forecasting service. Recognizing the importance of tropical meteorology, he was instrumental in founding the Institute of Tropical Meteorology at the University of Puerto Rico. He also reorganized the American Meteorological Society and established the Journal of Meteorology and later, in Sweden, the geophysical journal Tellus.

Rossby became increasingly active in promoting international collaboration in the late 1940’s. At the request of the Swedish government, he returned to Sweden in 1950 and organized the International Meteorological Institute. He continued to make extended visits to the United States during the 1950’s, mainly in connection with his work at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.

Despite his strenuous work as organizer, director, and promoter, Rossby still found time and energy for high-quality research. His original contributions to meteorology reveal a deep insight into the fundamental processes taking place in the atmosphere and oceans. He produced many new ideas that he submitted for discussion to the group of scientists working around him, often approaching a complex problem by introducing bold simplifications to be accounted for later.

During the 1920s Rossby worked on atmospheric turbulence and the theory of atmospheric pressure variations. While at MIT he continued his research on atmospheric and oceanic turbulence and introduced the concepts of mixing length, the roughness parameter, and the logarithmic wind profile. During his early years at MIT, Rossby applied thermodynamics to air mass analysis, a subject first systematically studied by T. Bergeron in 1928. Rossby designed a graphical method, the Rossby diagram, for the identification of air masses and the processes that give rise to their formation and modification (1932).

Pursuing a method advocated by W. N. Shaw during the 1920’s, Rossby and his collaborators developed the technique of isentropic analysis. Using this technique, which allowed the tracing of large-scale air currents, Rossby started his studies of the dynamics of the general circulation of the atmosphere. In connection with a project on long-range forecasting started in 1935, he began to investigate the circumpolar system of long waves, now called Rossby waves, in the westerly winds of the middle and upper troposphere.

These waves exert a controlling influence on weather conditions in the lower troposphere. Rossby developed a dynamic theory of these long waves on the basis of the theorem of conservation of absolute vorticity (propounded by Helmholtz in 1858) and derived a simple formula, now called the Rossby equation, for their propagation speed (1939, 1940). This formula became perhaps the most celebrated analytic solution of a dynamic equation in meteorological literature.

Rossby’s theoretical analysis profoundly influenced both applied and theoretical meteorology and oceanography during subsequent decades. The applicability of his theoretical results convinced Rossby that the principal changes in the atmospheric circulation could be predicted by considering readjustments of the horizontal velocity field without taking into account changes in the vertical structure of the atmosphere. In 1940 he and his collaborators carried out the first numerical predictions for a “one-layer” barotropic atmosphere in which vorticity was conserved. These calculations and the introduction of high-speed electronic computers during the 1940’s set the stage for the simultaneous development of forecasting techniques and theory through comparisons of calculated and observed atmospheric states, as Bjerknes had envisioned in 1904.

Back in Stockholm, Rossby continued to work on problems of atmospheric and oceanic circulation and their interactions. In addition, he began to study geochemistry in general and atmospheric chemistry in particular, seeing it as an opportunity to broaden the scope of meteorology. He organized an international network for the investigation of the distribution of trace elements in the atmosphere.

Rossby’s major achievements that he made in the field of oceanography contributed greatly to the understanding of heat exchange in air masses and atmospheric turbulence and investigated oceanography to study the relationships between ocean currents and their effects on the atmosphere. Rossby’s major works on the thermodynamics of atmospheric processes and atmospheric turbulence greatly influenced the development of mathematical models of general atmospheric circulation and numerical weather forecasting. He established the existence of long waves in the upper atmospheric layers (Rossby waves) and developed the theory for their movement. He laid the foundations for the theory of atmospheric jet streams and studied the interrelation between atmospheric and oceanic processes. Rossby’s works were the first to deal with atmospheric chemistry and atmospheric radioactivity.

Under Rossby’s leadership, the research group at Chicago became engaged in synoptic, theoretical and experimental studies of the general circulation and developed most of the basic concepts of the jet stream, the core of high-speed winds embedded in the upper long waves, and it was first revealed in the late nineteenth century by observation of the drift of cirrus clouds but was systematically encountered and investigated only as a result of the establishment of a worldwide network of upper-air sounding stations during World War II. In analogy to his work on ocean currents (1936), Rossby found a partial explanation for the existence and maintenance of the observed latitudinal wind distribution that was based on the concepts of large-scale lateral mixing and conservation of absolute vorticity (1947).

In 1948 he founded and became director of the Institute of Meteorology at the University of Stockholm. From 1954 he was president of the International Association of Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics.

He also developed the theory of Rossby wave movement. He worked on mathematical models for weather prediction and introduced the Rossby equations, which were used in 1950 with an advanced electronic computer to forecast the weather.

Rossby’s contributions to meteorology were noted in the December 17, 1956 issue of Time magazine.

Rossby's research interests included polar front theory, atmospheric flow, atmospheric turbulence, dynamics of the stratosphere, thermodynamics, ocean currents, jet streams, and vortices.

In 1943 Rossby was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences. He was also a member and then elected a President of the American Meteorological Society (1944–45).

Quotes from others about the person

Phil Thompson: "Of course, Rossby was legendary as a spellbinder and I was completely taken in. I went away from that lecture thinking that meteorology was the most interesting and the most challenging field of science there was. Up to that time… I had no contact with the science of meteorology as such, at all."

Joanne Simpson: "One of the things that I admire in retrospect about Rossby, that although everybody thinks that Rossby was a theoretician, he actually also believed in being an observer and being a naturalist. He had a strong requirement, or at least recommendation, that everybody who was going to get a Ph.D. in meteorology ought to be either a private airplane pilot or glider pilot or a sailor."

George Benson: "He was a dynamic person, always living for the moment, full of ideas. He could get absorbed in a subject and forget everything else with the excitement of the intellectual challenge of the moment."

Athelstan Spilhaus: "I decided that if I was going to go into the airplane business, I had better understand the medium. So after I graduated, and took one degree in aeronautics (in 1932), I went upstairs in the Guggenheim Building (at MIT) and there was Rossby and his meteorologists, a wonderful little department with about as many professors and instructors as there were students. But both professors and instructors were excellent and students were excellent. The names of my fellow students, they're well-known in meteorology, great people. You mentioned Horace Byers, later of Chicago, Jerome Namias, R. B. Montgomery, an oceanographer, Chaim Pekeris, a very great theoretician - these were my fellow students, so the whole atmosphere was absolutely stimulating. I always think of Rossby as being a man among those who shaped my life. And the lives of many others, I'm sure, in meteorological business."

Verner Suomi: "He was a wonderful teacher. You see, what he was able to do which most of the other professors were not able to do as effectively as he was able, and that is, he would present the problem verbally. Then he would present the problem graphically. And you could see the solution, graphically. Then he would present the problem mathematically. But the mathematics came LAST, not first. Very effective teaching. I remember his going pretty fast through a lecture and he had a piece of paper in his hand in which he seemed to be looking at. He just crumpled it up and threw it onto the table there, so after class I went up and grabbed it. All it said on there was, "Today, do not talk about turbulence."

C. C. Wallen: "Carl-Gustaf Rossby was well-known for his ability to convince authorities for the need of further development of meteorology, and for funding."

After moving to the United States and living there for more than twenty years, on September 2, 1929, Rossby married Harriot Alexander and obtained American citizenship in 1939. They had three children: Stig Arvid, Hans Thomas, Carin.

March 12, 1906 – May 22, 1998, an American meteorologist who pioneered in aviation meteorology, synoptic weather analysis (weather forecasting), severe convective storms, cloud physics, and weather modification. Here is what he once said about his work with Rossby: "Horace Byers: In 1928, I received a call from the Chief Engineer of the Port of Oakland telling me that there was a man by the name of Carl-Gustaf Rossby, a very congenial Swede… He was looking for a meteorological assistant. I accepted the position and Rossby and I operated the model airway of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics on the airway between San Francisco, Oakland and Los Angeles."

Joanne Simpson (formerly Joanne Malkus, born Joanne Gerould; March 23, 1923 – March 4, 2010) was the first woman in the United States to receive a Ph.D. in meteorology, which she received in 1949 from the University of Chicago.

December 6, 1915 – 30 July 1995, a Finnish-American educator, inventor, and scientist. He is considered the father of satellite meteorology. He invented the Spin Scan Radiometer, which for many years was the instrument on the GOES weather satellites that generated the time sequences of cloud images seen on television weather shows. The Suomi NPP polar-orbiting satellite, launched in 2011, was named in his honor.