Background

Staudinger was born March 23, 1881, in Worms, Germany, to Dr. Franz and Auguste (Wenck) Staudinger.

1951

Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

Staudinger with his family. From left to right: Hilde Rüegg-Staudinger, Dora Lezzi (at the back), Luzia Kaufmann (in front), Hermann Staudinger, Urs Rüegg (between his knees), Peter Kaufmann (at the back), Eva Lezzi-Staudinger, Hansjürgen Staudinger (at the back), Klara Kaufmann-Staudinger, Gabriele Staudinger-Schwarz, statue of Franz Staudinger (father of Hermann)

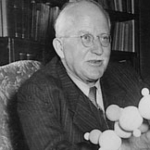

1953

Hermann Staudinger with polymer molecule model

Staudinger graduated from the University of Halle with Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1903.

Karlsruhe, Germany

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, where Staudinger had been working as an associate professor for five years from 1907.

Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland

Staudinger served as a professor at Swiss Federal Institute of Technology from 1912 till 1926.

Fahnenbergplatz, 79085 Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

Staudinger was a director of chemical laboratories at Albert Ludwigs University of Freiburg from 1926 to 1951.

Hermann Staudinger with Dutch physicist Frits Zernike

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

chemist educator scientist writer

Staudinger was born March 23, 1881, in Worms, Germany, to Dr. Franz and Auguste (Wenck) Staudinger.

Staudinger graduated from the Gymnasium at Worms, Germany in 1899 and began his university studies at the University of Halle under the guidance of the botanist Professor Klebs. While there, Staudinger began a lifelong detour from his original interest in botany. His family encouraged him to study chemistry to provide a strong background for his biological investigations, and he not only took their advice, but actually stayed in chemistry for most of the rest of his career. He studied in Darmstadt under the direction of professors Kolb and Stadel, and in Munich under the direction of Professor Piloty. In 1903 Staudinger finished his doctoral work under the direction of Professor Vorlander at the University of Halle. Although Staudinger had begun his studies in the analytical subdivision of chemistry, Vorlander’s influence and ideas caused him to develop an intense interest in theoretical organic chemistry. His doctoral thesis was on the malonic esters of unsaturated compounds.

Staudinger’s organic chemical investigations were relatively routine, although they resulted in the synthesis of some interesting new classes of organic molecules. In 1905, while in his first teaching position as an instructor with chemist and professor Johannes Thiele in Strasburg, he discovered the first ketene (colorless, poisonous gasses). Ketenes as a class are extremely reactive — they even react with traces of water and the oxygen in the air — and Staudinger and other researchers investigated their properties and chemistry for several years. In 1907 he prepared a special dissertation on the ketenes and was awarded the title of assistant professor. Shortly thereafter, he accepted an associate professor position at the Technische Hoshschule (now Karlsruhe Institute of Technology).

Staudinger began many basic organic synthesis projects in Karlsruhe, including a new synthesis of isoprene (a constituent part of rubber), although some of the newer projects slowed when he moved to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule) in Zurich in 1912. The Zurich position was a prestigious one, but the teaching load was many hours per week, so he curtailed his research in some areas. He proved to be a dedicated teacher and instilled in his students an appreciation not only for chemistry, but also for the power of technology in society.

During his fourteen years in Switzerland, Staudinger continued investigations on the chemistry of the ketenes, oxalyl chloride, and several materials that are shock-sensitive, that is, they explode when bumped or dropped. He also continued work on pyrethrin insecticides, and when they could not be easily synthesized, drew on his botanical interests and suggested that new strains of chrysanthemum (from which natural pyrethrines are extracted) might yield better quantities than any laboratory. During World War I much of Staudinger’s work was driven by wartime shortages. He investigated the aromas of pepper and coffee to see if synthetic substitutes could be produced for those foods, and attempted to synthesize some important pharmaceuticals. He was successful enough to patent some of the artificial flavors and fragrances, although generally they proved uneconomical if the natural material was available.

In 1926 Staudinger accepted a position as director of the chemical laboratories at Freiburg University (officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg), where he remained until his retirement in 1951. The move to Freiberg University signaled Staudinger’s break with traditional organic chemistry. He had first proposed the idea of macromolecules in 1920 while still in Zurich, but at Freiberg he gave up most of his other chemical research to pursue the study of rubber and synthetic polymers. It was a decision which caused his colleagues some consternation because he was well respected in his field, and they felt he would do damage to his reputation by working on such unpromising materials from such an unorthodox point of view.

With carefully designed experiments, Staudinger gradually accumulated evidence that a group of extremely large molecules existed. They did not comprise oddly associated clumps of smaller molecules, and were not themselves single unit cells. Instead, these molecules resembled chains of repeating units, strung together and bonded to each other — like pearls on a wire. Additionally, because any number of units might be bonded together during synthesis, these large molecules had differing molecular weights, depending on the length of the chain. While working in this area, Staudinger developed some new analytical methods and discovered a relationship between the viscosity of a polymer solution and its molecular weight. He had developed the method in desperation when he could not get funding for more sophisticated equipment, but it was soon widely used in industry because it was inexpensive, fast, and accurate. The equation, now called Staudinger’s Law, allows a fairly simple estimation of molecular weight by measuring the “drag” or “stickiness” of a liquid flowing through a small tube (viscosity).

During World War II, the Freiburg University chemistry facilities were virtually destroyed in an Allied air bombardment in November, 1944, and it was several years before they were fully operational again. Staudinger’s work slowed after the enormous stresses of the war, although he still found the energy to start and edit two new journals, one on macromolecular chemistry. He gave many talks and wrote prolifically on the subject of macromolecules until the end of his career.

As time went on, however, evidence from other areas of scientific study built unequivocal support for macromolecules. Staudinger had speculated for years that living systems must require macromolecules to function, and the new science of molecular biology began to lend vigorous support to that idea.

Staudinger was also a prolific writer, among his books were Die Ketene (Ketenes), published in 1912; Anleitung zur organischen qualitativen Analyse (Introduction to organic qualitative analysis); Tabellen zu den Vorlesungen über allgemeine und anorganische Chemie (Tables for the lectures on general and inorganic chemistry); Die hochmolekularen organischen Verbindungen, Kautschak und Cellulose (The high-molecular organic compounds, rubber and cellulose); Organische Kolloidchemie (Organic colloid chemistry); Fortschritte der Chemie, Physik und Technik der makromolekularen Stoffe (Progress of the chemistry, physics and technique of the macromolecular substances), jointly with Professor Vieweg; Makromolekulare Chemie und Biologie (Macromolecular chemistry and biology); Vom Aufstand der technischen Sklaven (The uprising of the technical slave), published in 1947. In addition, Staudinger edited the periodical Die makromolekulare Chemie (Macromolecular chemistry). In 1961 his book Arbeitserinnerungen (Working memoirs) appeared. Besides the books, Staudinger published a great number of scientific papers.

Hermann Staudinger’s interest in organic chemistry was wide ranging and he made many important contributions in that field. He is best known for his concept of the "macromolecule". Since 1920 Staudinger had written approximately 500 papers on macromolecular compounds, about 120 of these on cellulose, about 50 on rubber and isoprene.

Staudinger won the LeBlanc medal given by the French Chemical Society in 1931, as well as the Cannizzarro Prize in Rome in 1933. He was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1953 for his discoveries in the field of macromolecular chemistry.

In 1999 Staudinger's work was designated as an International Historic Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society and Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker.

Staudinger was a member and honorary member of many Chemical Societies and the Society of Macromolecular Chemistry in Tokyo.

Spirited discussions bordering on uproar often greeted Staudinger when he gave scientific lectures; his persistence and patience in the face of such hostility became legendary. Historians have noted such resistance before on the part of the scientific community whenever a truly revolutionary idea is advanced.

In 1906 Staudinger married Dorothea Förster. They had four children - Eva, Hilde, Hansjürgen and Klara. Staudinger and Dorothea divorced after 21 years of marriage in 1925. After the divorce Staudinger stayed in touch and on good terms with his family. Staudinger married Magda Voita two years later.

His father was a philosopher and professor at various German institutions of secondary education, and was interested in social reform.

His wife was a plant physiologist who often participated in Staudinger's research, collaborated in writing many of his papers, and made some important connections of her own between his macromolecular theories and the molecules of biology. Staudinger listed some of her considerable contributions in his Nobel Prize address, and dedicated his autobiography to her.

He was Staudinger's doctoral advisor.