Background

Thomas Girtin was born in Southwark, London, the son of a well-to-do brushmaker of Huguenot descent. His father died while Thomas was a child, and his mother then married a Mr Vaughan, a pattern-draughtsman.

Thomas Girtin was born in Southwark, London, the son of a well-to-do brushmaker of Huguenot descent. His father died while Thomas was a child, and his mother then married a Mr Vaughan, a pattern-draughtsman.

Born in London, Girtin learned drawing as a boy under Thomas Malton, and was then apprenticed to Edward Dayes, a topographical watercolorist and mezzotint engraver. His early drawing was exceptional, containing a good deal of the vigour of Gainsborough and the range of Cozens, and while it may be true that J.M.W. Turner recognized his drawing skills and encouraged him to paint landscapes

Girtin began exhibiting his landscape painting at the London Royal Academy from 1794. His topographical and architectural sketches soon established his reputation, and his natural talent for watercolors caused some critics to see him as the new leader of Romantic watercolor art. He took numerous sketching trips into the English countryside, visiting North Wales, the Lake District, Yorkshire, and the West Country. By 1799, he was attracting influential patrons such as Lady Sutherland, and the art collector Sir George Beaumont. He was also a leading member of the sketching society known as the Brothers.

By 1801 he was a familiar guest at country houses owned by his art patrons, such as Mulgrave Castle and Harewood House and commanded fees of 20 guineas and upwards for a painting. His health, however, was beginning to fail. In the Autumn and winter of 1801 - 1802 he spent several months in Paris, completing a series of watercolor views of the city which were duly issued in a set of engraving (T"wenty Views in Paris and its Environs") the following year. Later in 1802, Girtin completed a monumental panorama of London - painted in oils and noted for its naturalistic treatment of urban light - called the Eidometropolis, which was exhibited to great acclaim.

It is not easy to explain exactly what Girtin did in watercolor, though it is easy enough to see when one studies a collection of early English water-colors. It is not enough to say merely that he gave a new boldness and breadth to the genre and expanded its colour palette, because Gainsborough had boldness, Cozens had breadth, and Francis Towne had an equally wide range of color. But he managed to combine all these attributes in a new and personal way, and thus imparted to watercolour painting a strength and substantiality which allowed it to withstand direct competition with oils, without in any way reducing its unique qualities. Above all, his control of the medium was greater that of any one who had preceeded him.

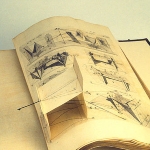

For example, his drawings were not made in the traditional linear style, to which tone and color were then added. Instead he conceived his pictures in terms of large washes to which the detail of drawing is added, and demonstrated an acute ability to see a painting as a single entity rather than a collection of parts. His subjects - typically architectural - are much more than visual chronicles of buildings or places: they are a pictorial expression of light and atmosphere. Another innovation was a new technique in the handling of his washes, as well as the ability to extract new qualities and beauty from the behaviour of watercolor on paper.

He was less experimental in his use of color. While the scenery of Northern England inspired him to employ a new watercolor palette of warm browns, slate greys, indigo and purple, and although his washes contained bold strong colour, his overall colour schemes were never entirely naturalistic. With his untimely demise in 1802, the first phase of English landscape painting came to an end. The next stage would see its transformation in the revolutionary painting and colorism of Girtin's contemporary J.M.W. Turner. Tragically, Girtin died in November 1802 at the age of twenty-seven. The cause was variously cited as tuberculosis, consumption or asthma. Paintings by Thomas Girtin hang in several of the world's best art museums, including the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum and The British Museum.

Girtin's beautiful landscape paintings in watercolour helped raise the profile of such subjects and his chosen medium during his short life. His remarkable talents were acknowledged by his friend and exact contemporary Turner. His most ambitious work, a lost panorama of London, is known from sketches in the British Museum, London.

A Gateway with Two Round Towers

1797A Lake and Mountains in Westmorland

1797Chichester Cathedral from the South West

1797Glasgow High Street, Looking towards the Cathedral

1797Interior of Lindisfarne Priory

1797Kidwelly Church, Caermarthenshire

1797Kirkstall Abbey from the North West

1797Lancaster

1797Lancaster Church and Bridge

1797Part of the Ruins of Walsingham Priory

1797Raby Castle, Co. Durham

1797Rochester Cathedral from the North East, with the Castle Beyond

1797Scene in the Lake District, near Buttermere

1797The Kitchen at Stanton Harcourt, Oxfordshire

1797The Ruins of Middleham Castle, Yorkshire

1797The West Gate, Canterbury, with Neighbouring Buildings

1797Trees near a Lake or River at Twilight

1797Tynemouth Priory from the Sea

1797A Winding Estuary

1798Jedburgh Abbey from the River

1798Thomas Girtin adhered to the artistic traditions of Romanticism.

He was the dominant member of the Brothers, a sketching society of professional artists and talented amateurs.

Quotes from others about the person

Had Tom Girtin lived, I should have starved.

In 1800, Girtin married Mary Ann Borrett, the 16-year-old daughter of a well-to-do City goldsmith, and set up home in St George's Row, Hyde Park, next door to the painter Paul Sandby.