Background

Wilhelm Friedrich Kühne was born on March 28, 1837, in Hamburg, Germany. He was the fifth of seven children. His father was a wealthy Hamburg merchant; his mother was interested in the arts and politics.

Wilhelmsplatz 1, 37073 Göttingen, Germany

In 1854, at the age of seventeen, he entered the University of Göttingen, where he studied chemistry under Wohler, anatomy under Henle, and neurohistology under Rudolf Wagner. Two years later he obtained the Ph.D. with a thesis on induced diabetes in frogs.

Wilhelmsplatz 1, 37073 Göttingen, Germany

In 1854, at the age of seventeen, he entered the University of Göttingen, where he studied chemistry under Wohler, anatomy under Henle, and neurohistology under Rudolf Wagner. Two years later he obtained the Ph.D. with a thesis on induced diabetes in frogs.

Royal Society, London, England

Kühne was a foreign member of the Royal Society.

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden

Kühne was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States

Kühne was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences, Berlin, Germany

Kühne was a member of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences.

A photo of Wilhelm Kühne.

A photo of Wilhelm Kühne.

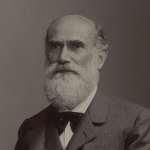

Group Portrait, from left to right E. J. Marey, A. Dohrn, C. Golgi, E. H. P.A. Haeckel, A. A. W. Hubrecht, W. F. Kuehne, H. P. Bowditch, Hugo Kronecker and H. Kronecker. Taken outside the Old Schools, Cambridge.

A photo of Wilhelm Kühne.

educator physiologist scientist

Wilhelm Friedrich Kühne was born on March 28, 1837, in Hamburg, Germany. He was the fifth of seven children. His father was a wealthy Hamburg merchant; his mother was interested in the arts and politics.

Kühne attended grammar school at Lüneburg, but preferred his own scientific experiments to the Latin grammar. In 1854, at the age of seventeen, he entered the University of Göttingen, where he studied chemistry under Wohler, anatomy under Henle, and neurohistology under Rudolf Wagner. Two years later he obtained the Ph.D. with a thesis on induced diabetes in frogs.

Kühne spent some time at the University of Jena, where he worked with Carl Gustav Lehmann on diabetes and sugar metabolism. In 1858 he worked in Berlin with Emil du Bois-Reymond on problems of myodynamics and with Felix Hoppe-Seyler, who was in charge of the chemical laboratory at the institute of pathology directed by Rudolf Virchow. His other associates there included Julius Cohnheim, W. Preyer, F. C. Boll, Hugo Kronecker, and Theodor Leber. In the same year, Bernard’s report on sugar puncture prompted Kühne to go to Paris, where he received many suggestions regarding scientific methods.

In 1860 he spent some time in Vienna working with Ernst Brücke and Carl Ludwig. Most probably it was Brücke who imparted to him his interest in the physiology of the protozoa and the nature of protoplasm. In 1861 he began his independent scientific career, succeeding Hoppe-Seyler as an assistant in the chemical department of Virchow’s institute. The latter gave him a completely free hand with his work. At the institute, Kühne did not investigate strictly pathological questions but dealt with cylophysiological problems. During the Seven Weeks’ War between Prussia and Austria in 1866, he was given charge of epidemic control. He left Berlin in 1868 to take over the chair of physiology at Amsterdam; Gustav Schwalbe and, later, Thomas Lauder-Brunton became his collaborators.

In 1871 Kühne succeeded Helmholtz in the chair of physiology at Heidelberg; his colleagues included E. Salkowski, J. N. Langley, and R. H. Chittenden. He continued to teach and do research there until his retirement in 1899. In 1875, on his initiative, a new building for the institute of physiology was built. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of Kühne’s appointment at Heidelberg (1896) a jubilee volume of the Zeitschrift für Biologie was published with contributions by E. Salkowski, J. von Uexküll, G. Schwalbe, Leon Asher, Lauder Brunton, and Kronecker.

Wilhelm Kühne went down in history as noted physiologist known for his work on the physiology of muscle and nerve, and the chemistry of digestion. He discovered the protein-digesting enzyme trypsin, and coined the word enzyme. He was also known for his research on vision and the chemical changes occurring in the retina under the influence of light. Kühne also pioneered the process of optography, the generation of an image from the retina of a rabbit by applying a chemical process to fix the state of the rhodopsin in the eye.

In 1862, at the instigation of Albert von Bezold, Kühne was awarded an honorary Doctor of Medicine degree by the University of Jena.

José Rizal, martyr and national hero of the Philippines, learned physiology under Kühne.

Kühne advanced research in the physiology of metabolism and digestion (sugar, protein, bile acids, trypsin), the physiology of muscle and nerves, the physiology of protozoa, and physiological optics. Many of his results and observations were immediately integrated into standard texts.

After presenting his doctoral thesis on induced diabetes in frogs, in 1856 Kühne elaborated a problem previously dealt with by Wohler, who had stated that the benzoic acid ingested in food is found in the urine in the form of hippuric acid. Kühne proved that this compound is produced in the liver.

While collaborating with du Bois-Reymond in Berlin, Kühne began to study problems of myodynamics, simultaneously applying physiological, microscopical, and chemical methods to arrive at some essentially novel findings. He investigated histologically the nature of the motor nerve endings (1868) and found their terminal organs, which exist as motor end plates in warm-blooded animals. In preparations of the sartorius, a muscle rarely used until then for experimental purposes, he established the two-way conductibility of the nerve fiber (1859) and the direct excitability of the muscle fiber by both electric and chemical stimuli.

From the sartorius Kühne obtained coagulable myosin; assuming the heat rigor of the muscle to be a clotting process, accompanied by a clouding of the muscle substance, he was led to believe that the living muscle must be viscous in consistency. He later fortuitously proved this assumption when he observed a nematode creeping forward in a living muscle fiber (1863). Kühne also ascertained that the myohematin myoglobin is related to hemoglobin and, having suspected that contractile elements were involved in the creeping motions of the amoebas, proved the electric excitability of monocellular organisms (1864). Through his research, Kühne demonstrated the extraordinary usefulness of cytophysiological investigations for the solution of problems of general physiology.

Beginning with his stay at Amsterdam, Kühne again turned to problems of physiological chemistry, especially those of digestion. In particular, he carried out investigations on the splitting of the large protein molecule during digestive fermentation. Since the stomach is not digested by its own pepsin, he concluded that such ferments have inactive protein precursors, which he called “zymogens”; he then traced the disintegration of proteins into albumoses and peptones. He further succeeded in demonstrating microscopic changes in living pancreatic cells during their activity. Having learned the technique of pancreatic fistula from Claude Bernard in Paris, Kühne pursued the study of the proteolytic effect of the pancreatic enzyme, which he called trypsin (1877).

Kühne’s Lehrbuch der physiologischen Chemie appeared in 1868. It clearly and concisely presented the state of the science at that time. In 1877 Kühne took up a completely different topic. In 1876 Boll had established that the layer of rods of the retina contain a purple pigment that disappears on exposure to light. On this basis Kühne supposed that there was a primarily chemical process that preceded excitation of the optic nerves; he demonstrated that the retina works like a photographic plate, with light bleaching out the visual purple, which is regenerated in darkness. He succeeded in producing his famous “optograms” - the reproduction of the pattern of crossbars of a window on the chemical substance of the retina of a rabbit (1877-1878). Kühne was thus the first to perceive the migrating pigments in the living retina. His assumption that a photochemical process occurs prior to the excitation of the retina led him to investigate the electric processes in the eye, thus linking his research with the work of du Bois-Reymond and Holmgren. It may be noted that Kühne’s research, as was typical of the work of German physiologists of the second half of the nineteenth century, always began with the formulation of a question rather than growing from a method.

Shortly before his death Kühne published a remarkable lecture on the responsibility of the physician to his patient and the relationship of medicine to science (1899). He postulated medical ethics as a subject in medical training, and he believed that both a sympathetic heart and a clear, keen mind were necessary qualities for a physician. He regarded the concept of the immortality of the soul as important to the attitude of the physician and anticipated an era in which medical science would have to adapt more to the needs of society than it had done until then.

Ida Henrietta Hyde wanted to study physiology under Kühne at the University of Heidelberg on the recommendation of Professor Alexander Goette at Strasbourg. The University accepted her, but Kühne refused to allow her in lectures and laboratories. He is reported to have said that he would never allow “skirts” in his classes. However, when a colleague asked him whether, if at the end of the course she could pass the examination, he would grant her the degree, he jokingly replied that he would. And so for six semesters, she had to study physiology independent of the classroom and of hands-on laboratory projects, using only his assistants’ notes and lab sketches. Finally, a four-hour oral examination by Kühne’s academic committee, proved her worthiness. The “Summa Cum Laude” degree, the highest honors, could not go to a woman, so Kühne invented a new phrase: “Multa Cum Laude Superavit," meaning “she overcame with much praise.”

Kühne was a foreign member of the Royal Society and member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences.

A man of great versatility, Kühne was fond of good company and associated with artists as well as scientists.

Kühne was married to Helene Blum, the daughter of a Heidelberg mineralogist.